JULY JOYS

MEMORIES OF DAYS OF DELIGHT AND REFLECTIONS ON OUR CHANGING WORLD

As I often do, when thinking about this month’s newsletter I did a bit of looking back to what I had offered for this month in years gone by. Amazingly (at least to me) I’ve been churning it out for a decade and a half. In that regard, just last week I had lunch with a charming lady who serves as the Vice President for Development at my undergraduate alma mater, King College in Bristol, TN (now King University). In the course of our far-ranging conversation she asked me if I ever had writer’s block or found myself at a loss when it came to producing words. I assured her that quite the opposite was the case and that I had ideas for books or major projects sufficient to last several lifetimes.

Hopefully that’s the case with this newsletter as well, although as those of you who have read it for years know, its subject matter tends to lean heavily on nostalgia; the nature of life in my boyhood and young manhood; and closeness to the good earth of the sort that comes from activities such as hunting, fishing, foraging, and growing one’s own food. Those activities have always been integral parts of my life, although advancing age and the physical decline that inevitably is an unwelcome companion of lots of years has meant considerable curtailing of my once seemingly boundless energy. Still, hammering out words on a computer doesn’t require much physical effort, and mentally I am either still somewhat competent or else a fine hand at self-delusion.

In reviewing past July newsletters, one of them utilized a grand Statler Brothers’ song, “Carry Me Back,” as a sort of its theme for as link to the past. I’d like to reprise portions of it in this newsletter along with blending in lyrics from a man whom I consider one of the topmost “greats” of country singing and songwriting, Merle Haggard. The song I have in mind is “Are the Good Times Really over for Good (I Wish a Buck Was Still Silver).” Its lyrics touch me deeply, and that’s especially true of these:

“When a man could still work and still would.”

“When a girl could still cook and still would.”

“When a Ford and Chevy would last ten years like they should.”

Beyond that there’s the strong theme of patriotism and pride running through the entire song. The Hag ends on an upbeat note, saying “the good times ain’t over for good.” I hope against hope he is right.

Yet I’d be a stranger to what I consider the truth if I didn’t admit I’m dubious. The work ethic and personal pride I knew as a boy seem to be slipping away like morning mist beneath Dog Days sun. Likewise, it seems there is more stress and less civility or common decency in today’s society than at any time in my life. I’m no prude, but the kind of language that has become commonplace would have earned a youngster a mouthful of Ivory Soap when I was a kid, and an adult using such language in most settings would have been condemned in no uncertain fashion. Similarly, there’s more whining, more “What’s in it for me?” attitudes, less faith, far more laziness, and a loss of something I’ve always held dear indeed, oneness with the good earth. In other words, on many fronts we actually seem to be “rolling downhill like a snowball headed for Hell” as some of Haggard’s lyrics put it.

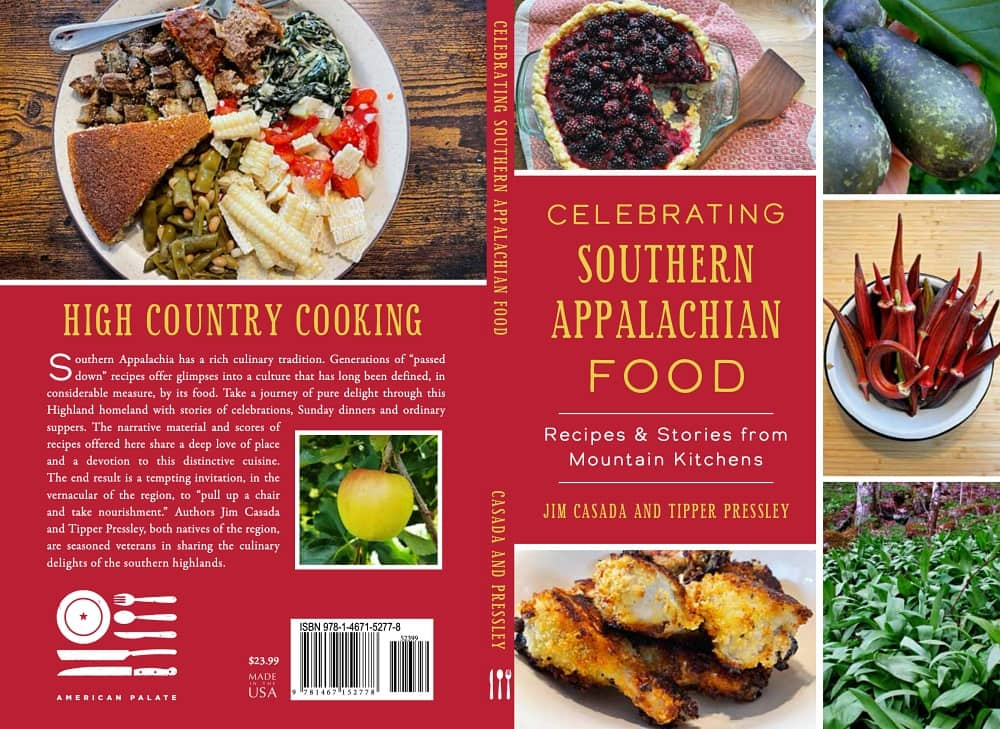

I mention this, at least in part, because my webmaster Tipper Pressley and I have at least broached the subject of a sort of sequel to the cookbook we wrote together, Celebrating Southern Appalachian Food: Recipes and Stories from Mountain Kitchens. Incidentally, the book has enjoyed a warm and gratifying reception, and you can order a signed, inscribed copy from my website (www.jimcasadaoutdoors.com). In talks about the work where Tipper and I have appeared at book signing events (the next one will be a drop in at the Marianna Black Library in my hometown of Bryson City, NC from 4 to 7 p.m. on August 22), I’ve regularly quoted lyrics from yet another grand songwriter, Canadian Ian Tyson. In his moving tribute to Western artist and writer Charlie Russell titled “The Gift,” Tyson has God offering these thoughts or motivation for Russell: “Get her all down before she goes. You gotta get her all down ‘cause she’s bound to go.”

Tyson’s underlying message, speaking through the voice of God, is that the Montana made for the wild man was fading fast. I fear the same is true for the way of life I knew growing up in North Carolina’s Great Smokies. Yet I feel with all the strength and every fiber of my being, and Tipper harbors similar thoughts, that there’s a great deal in that culture and approach to daily living that is worthy of celebration and preservation. Call me hillbilly if you wish, but if that involves the folkways and lifestyle which I knew in my highland homeland it’s a badge I’ll wear with a sense of honor approaching sheer reverence.

One way of making sure our Appalachia endures is through sharing traditional recipes, but others include describing and utilizing the countless ways in which our forebears lived. Those embrace the planting, cultivating, harvesting, preserving, and ultimately, eating of foodstuffs. They likewise involve recognition of the manner in which enjoying nature’s abundant bounty in the form of fish, game, and the vast larder of the wilds awaiting those with sufficient knowledge and gumption to find and forage, catch and kill, much of what they ate. It also means reflection on vanishing folkways—maybe knowing how to sharpen a knife or ax, find lighter wood (fat pine) and use it to get a fire going, growing a lot of what you eat, helping others who need a hand, greeting work as something that is meaningful and meritorious, and so much more.

If we can share these and many other ways from bygone days, doing so in a sort of Foxfire books fashion but with a more structured approach and with recipes to accompany all we cover, then maybe, just maybe, we can “get her all down before she goes.” In that regard, I’ve got a heartfelt request for each and every one of you. I would be deeply appreciative and I’m confident Tipper concurs with my sentiments, if you, as readers, would share with me your thoughts and suggestions on traditional folkways you feel richly deserving of preservation. That might come in the form of some family or community tradition, mention of a foodstuff or maybe a recipe, gardening or food-gathering tricks, old-time weather wisdom, or indeed anything along the line of closeness to and direct involvement with life lived in communion with nature. Just send your thoughts to me via e-mail (jimcasada@comporium.net). I plan to read and ponder your collective wisdom and rest assured that it will be deeply appreciated as planning for a sequel to Celebrating Southern Appalachian Food moves along. Or to put it another way, I’m asking you to help me, and Tipper, to capture some of those things that are not only “bound to go” but which already are going all too rapidly.

Now, let me change gears and harken back to the Statler Brothers and the song I mentioned at the outset. I come from what could probably be described as a musically gifted family. My sister has always had a pleasant singing voice, played the piano well when she was younger, and understands all the finer aspects of music. My brother has a decent voice, can make a harmonica talk quite nicely, and has even dabbled with a bit of song writing. One of his sons holds a Ph. D. in music (clarinet) and another one pulls guitar strings quite nicely, has a melodious voice, and is generally gifted in a musical sense. My daughter helped “sing” her way through college on a partial voice scholarship and subsequently performed with the Charlotte Oratorio Singers for a number of years.

Then there’s this forlorn soul, a total stranger to singing a tune (any tune) on key as well as being unable to do anything other than memorize lyrics and be front and center when it comes to pickin’ and grinnin’ sessions. I’m so hopeless, in fact, that a good friend who is also an exceptional musical talent (Rob Simbeck, an established Nashville presence who for many years wrote the narrative for the weekly American Country Music Countdown program), once told me: “Jim, you sing like a bird. A vulture.” Alas, that pretty well sums it up, and I reckon the closest I’ll ever come to any meaningful linkage with music is a modest ability I had in younger and sprightlier days to clog or buck dance. Of course with advancing years that high-energy activity has vanished like a dust devil dancing across a dry field that was recently plowed.

Still, for all my total lack of musical talent, I love songs, especially when traditional country and bluegrass music is involved. I grew up listening to WSM out of Nashville and the Wayne Raney show on WCKY in Cincinnati, Ohio. We didn’t have a television in our house, but the old radio where we listened to “Gunsmoke” and other programs, as well as college basketball and football games, picked up the above-mentioned 50,000-watt stations loud and clear. That boyhood love of music has never left me, and I do have one tiny bit of talent in this arena of life. Thanks to a good memory I know the lyrics to hundreds, probably thousands, of country songs. I may not have achieved quite the status David Allen Coe suggests when, in one of his songs, he says he knows the words to every song Hank Williams ever wrote, but I’m familiar with a passel of ‘em.

As I noted at the outset, lyrics from one such song came to my attention in browsing old newsletters, and every since, as I do a bit of advance planning for the 63rd reunion of my high school class (I guess I just revealed my age and obviously the numbers of what was a class of less than a hundred have dwindled appreciably). That’s the Statler Brothers “Carry Me Back,” which does take my mind down a long, winding road into the past. As I suspect is fairly common for those who grew up in small towns or rural areas and attended small schools (mine was the only public high school in the county although there was a second one serving the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians), a number of us have stayed in contact over the decades. There’s something about growing up country and being part of a tight-knit community that forms bonds seldom found in sprawling metropolitan areas. This morning, with that in mind and as earlier today as I picked what is pretty much the last hurrah for this year’s blueberry crop, I mediated and now muse on the Statlers.

I’ve always been passing fond of the group, and there are several reasons why that is the case. For starters, we are very much of an age, and the times and things which loom large in their songs forge a common bond. Similarly, they are sons of the Appalachian soil (Staunton, Virginia) like me, and we share small town roots, values, and memories. Their music has gospel origins similar to the sort of music making which was a Friday night fixture during the late 1950s in the area of the Smokies where I grew up. Then too, I love the fine harmony, the nice blend of humor and nostalgia which characterizes so many of their songs, and the fact that they sing of things with which I can identify.

Now appreciably beyond the Biblical allotment of three score and ten years, I’m increasingly inclined toward the way of thinking provided in the lyrics of “Carry Me Back.”

Carry me back and make me feel at home.

Let me cling to those memories that won’t let me alone.

When it was always summer and she was always kind.

Carry me back Lord, while I still got the time.

There’s even fading memories of a teenage girlfriend who likely would, to this day, remember 1959. We had a local hamburger joint, driving around town or going to the drive-in movie were standard summertime activities, and preachers did indeed visit poor souls when they got down.

Such things were part and parcel of growing up in a rural, small town setting, and if you had similar experiences in youth, no matter what your age today, I have to reckon you were blessed. I also strongly suspect that you may be troubled, perhaps a great deal, by what seems to be the gradual fading away of a sound work ethic, honesty, faith, patriotism, and caring for one’s neighbors as integral parts of daily life.

The July memories I cling to are many and varied, but without exception they are warm, winsome ones. Recently I’ve been writing a series of newspaper columns reminiscing about my boyhood interaction with the small but vibrant local black community, and thinking of some of those wonderful souls and the setting stirs me deeply. Precisely the same is true for a time when a youngster could thumb a ride without any concern, took summertime work (mowing lawns and performing other yard work, weeding and hoeing gardens, helping parents and grandparents, and maybe from about the age of 14 or so on holding a full-time seasonal job) as a matter of course. I did that, and the same was true for everyone I grew up with. Summer meant fun and three months freedom from school, but it also meant putting some honest sweat on one’s brow.

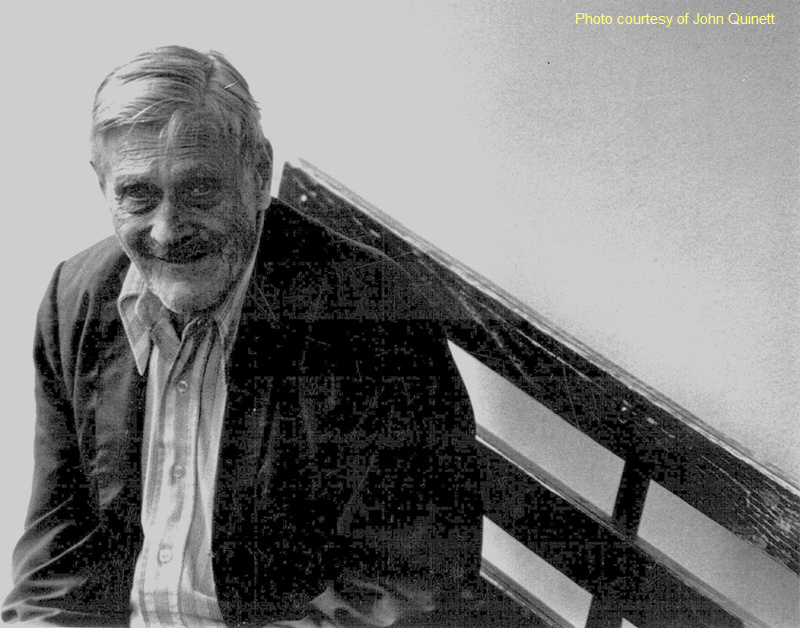

Al Dorsey

On a different front, books were constant and welcome companions throughout my youth. That’s never changed, but in July they were reserved for rainy days and evenings. There was simply too much to do outdoors, both working and playing, the rest of the time. Seldom did a day pass when I didn’t put in three or four hours either in a local trout stream or on the banks of the Tuckaseigee River, where catfish were my primary quarry. I ran trot lines and throw lines in the river, occasionally sold some catfish, and spent a world of time with an old river rat named Al Dorsey. Later I would learn that old Al, who was a stranger to soap and warm water but a catfishing wizard, had spent upwards of a decade in the state pen following a conviction for second-degree murder. As I knew him though, he was just a smelly old codger, one among many local characters who were part and parcel of my boyhood.

I got to know several other intriguing characters thanks to spending idle hours at a shady spot near the town square where old men played checkers, swapped lies, and trade knives. The gathering site had two names, both of them grand examples of the pity, to-the-point way mountain folks tend to talk. The polite name for the place was “Loafer’s Glory,” but another off-color term was used more frequently. This was “Dead Pecker Corner,” a humorous reference to the age and declining sexual interest and/or prowess of the old-timers who were regulars there.

That self-same square was also frequented on Saturdays during the summer by various persuasions of Bible thumpers. Some of these street preachers, with their powerful voices and verbal depictions of hell-fired and damnation, could draw quite a crowd. Others garnered scant attention but preached on bravely nonetheless. Often I would stop to listen to them a bit, not so much for the message as for the show.

Religion had other summertime faces as well. There were local tent revivals about every other week, and often part of the event would be some exceptional gospel singing. Similarly, once or twice a summer there would be sort of offshoots of the traditional brush arbor revivals, with an entire Saturday being devoted to preaching, singing, and dinner on the grounds. Later, a few years after I had gone off to college, a local gospel group which attained international renown, The Inspirations, would turn this into an annual event known as “Singing in the Smokies.” The original members of the group were just local guys to me—Archie Watkins, the tenor, was the son of the school custodian, and I dated one of his sisters for a time; Martin Cook had been a high school teacher; while the other original members, Jack Laws, Ronnie Hutchins, and Troy Burns; were all simple sons of the Smokies who made a prominent place for themselves in the world of gospel music.

Most of the time when I listened to street preachers it was after having attended the Saturday matinee at the local movie theater. For a thin dime (later inflation took the price to 12 and then 15 cents) you got the latest installment of a serial, a cartoon, a news reel, and a Western featuring the likes of Johnny Mack Brown, Lash LaRue, the Lone Ranger, Roy Rogers, or Gene Autry. In July I was usually comparatively flush with money, thanks to the fact that blackberries peaked in ripeness around Independence Day and also because I caddied on the local golf course, mowed lawns, caught and sold night crawlers and spring lizards to bait stores, and earned pocket money in various other ways. Sometimes I’d make as much as five or six dollars a day, particularly in my later teens when I held a full-time job. For a boy in that day and setting, I was in high cotton. It was a grand time in my life and in the nation, back when, as Merle Haggard put it in the above-mentioned song, “before Viet Nam came along” or “Nixon lied to us all on TV.”

Mostly though, “those memories that won’t leave me alone” have little to do with the national scene. Instead, they are about ordinary things which somehow, with the passage of time, have turned extraordinary. Here’s a sampling, and I’d encourage you, as you read, to look back to the same time in your life and resurrect those teenage memories etched indelibly on the slate of your mind.

*The first really big trout I caught—I still have a grainy black-and-white picture of it Momma insisted on taking, and for that as so many other simple but singularly meaningful things I owe her a lasting debt of gratitude.

*My first trout on a fly, which I ate with a special sort of “putting meat on the tale” sense of satisfaction that no trout before or since has ever provided. Incidentally, I’ve always been more of the “release to grease” or “hook to cook” persuasion than of a catch-and-release bent. When I was a youngster, both fish and game were welcome additions to the family diet.

*Flirting with tourist girls spending a few days in the mountains.

*Taking perverse joy in giving a flatlander “Floridiot” (what Floridians were called, behind their back) directions to the Park which were inaccurate and would lead them to the dead end of what was known as the “New Road” and later became “The Road to Nowhere” because it was never finished. This was admittedly mean, but when folks asked questions like “Where do we see the bears?,” “Do they really make moonshine here?,” or “Are there wild Indians on the Cherokee Reservation?”, the temptation to pull some city slicker’s string was irresistible.

*Speaking of tricks, another one was to somehow convince visitors from the city to bite into a green persimmon. Talk about pucker power!

*Backpacking into a remote campsite in the Smokies and catching scores of trout every day while never seeing another soul except the buddies with whom I was camping.

*Playing fast pitch softball on warm evenings under the lights and being warmed in a different way by thoughts of your girl friend sitting in the bleachers watching the game.

*Feeling that a 25-cent milkshake or a 25-cent hamburger with all the trimmings were the finest fare imaginable.

*Going to square dances on Saturday nights and kicking up one’s heels to classic dancin’ tunes such as “Down Yonder” and “Under the Double Eagle.”

*Looking at the new fall edition of the Sears & Roebuck catalog, which always showed up about mid-July, and picking out one or two items which Mom would buy as part of my wardrobe for the new school year.

*Eating corn-on-the-cob to my heart’s content, and that usually meant a minimum of three ears of Hickory Cane or four of the smaller “sweet” corn.

*Spending several days at the home of some older cousins who lived all of six miles away. To me it seemed like another world.

*Practicing marksmanship for hours on end with a slingshot I had made (with some expert assistance from my Grandpa Joe).

*Skipping rocks in the river in hotly contest competitions with other boys to see who could get the most skips.

*Picking blackberries and enjoying the fruit of my labors in the form of goodness straight from nature’s rich larder (see recipes below).

*Having my heart broken, repeatedly, in those stumbling, sensitive, and singularly uncertain times of teenage romance.

*Enjoying an icy slice of watermelon with Grandpa Joe after a long, hot session of garden work, then listen to him chuckle at my efforts to become a master of seed spitting. Incidentally, that particular memory makes me wonder what ever happened to the giant green, round watermelons we knew as “cannon balls” and to lament the passing of other melons, such as Charleston Greys, which had plenty of seeds for spitting. Today about all you can find is sissy pants pretenders to watermelon wonder in the form of comparatively insipid and tasteless “seed free” melons.

*Riding truck inner tubes in the creek while scanning overhanging limbs for water snakes (not a problem) and hornets’ nests (a major problem if you disturbed a nest).

All these memories, and many more, course through my mind as I become ever longer in the tooth and sparser (and greyer) in the hackle. Still, as the lyrics of “Carry Me Back” suggest, they “make me feel at home” and I’m glad to share them “while I’ve still got the time.” I suspect many of you have similar memories, whether they are ones which carry you back or those currently in the making. Either way, I hope you are as blessed as me in terms of having had Julys aplenty filled with wonder.

JIM’S DOIN’S

My regular “Wisdom and Ways” column in the summer issue of Carolina Mountain Life was on “The Enduring Pleasures of Pickin’ and Grinnin’” (pages 51-52) and my most recent Books column in the July/August issue of Sporting Classics is “Theodore Roosevelt as an Outdoor Writer” (pages 118-23).

RECIPES

MAKINGS FROM MATERS

Tomatoes loomed mighty large in family fare during my youth, and Daddy went to a great deal of trouble to make sure his plants were highly productive. That mean religious preparation of the ground before putting the young plants in the ground; pruning, staking, and tying the plants as they grew; taking all possible steps to avoid blight and blossom-end rot; and more. Momma did her part by canning tomatoes, tomato juice, and soup mix. The same held true for my late wife, and she expanded my tomato horizons a good bit with some interesting recipes. Here are several recipes, some of which appear in Celebrating Southern Appalachian Food and others from Fishing for Chickens: A Smokies Food Memoir.

TOMATO PIE

Pre-bake individual phyllo shells

Sauté a small onion in cooking oil

Fresh basil

Slice tomatoes fairly thin and lay them atop paper towels. Salt the tops and let sit ten minutes before patting them dry.

For the topping, shred two cups of sharp cheddar (Cabot Seriously Sharp is a good choice). Mix with ¾ cup of real mayonnaise, adding salt and pepper to taste (remember that the tomatoes have been salted and even though the patting will remove some of it a salty tang remains).

Layer tomatoes, then onion and basil, then another tomato layer and spread topping to fill each phyllo shell to the top. Bake at 375 degrees for 30 or so minutes or until done.

TOMATO DILL SOUP

1 stick butter

1½ large onions pureed in a food processor

¼ cup fresh garlic, minced

1½ teaspoons dried dill

¼ tablespoon kosher salt

1/8 tablespoon black pepper

9 cups tomatoes (crushed or diced—that is two 28-ounce cans plus one 14½–ounce can, or use

a comparable amount of ones you have canned or frozen)

3 cups water

2 cups heavy cream (a pint of half-and-half with some whole milk added will also work)

Place butter, onions, garlic, dill, salt and black pepper in a large covered pot. Sauté on low heat until onions are translucent. Add tomatoes and water. Simmer for one to two hours. Remove from heat and blend in cream.

TOMATOES AND EGGS

Slice away the bottom quarter of a large tomato and carefully remove any core that remains in the large section, which needs to have a cavity large enough to hold an egg. Place the tomato “container” atop a greased baking sheet or pan, bottom side down, and carefully break a small or medium egg into the opening at the top. Bake at 350 degrees until the egg sets at a point just short of the consistency your desire. Remove from the oven, sprinkle liberally with sharp, shredded cheddar cheese, then place back in the oven until the cheese melts. Eat piping hot.

BAKED CHEESY TOMATOES

Slice away the bottom of tomatoes and then sprinkle liberally with a mixture of Parmesan cheese and bread crumbs. You can buy crumbs but heels from a loaf of bread, given a quick whirl in a processor, are much cheaper and work just as well. Bake at 375 degrees until the cheese/bread topping begins to turn brown and eat hot from the oven. If you have them, use leftover biscuits or cornbread as an alternative crumb base.

TOPPED TOMATOES

I can take two hefty slices of a dead ripe tomato (and to me a hefty slice is a half inch thick) and have the base for a meal. Top those slices with various offerings such as stewed corn cooked with a bit of bacon grease, hamburger gravy, crowder peas hot from the stove, or slip the slices between a pair of sho’ ‘nuff cathead biscuits and you are knocking on the gates of culinary heaven.