APRIL NEWSLETTER

OF BOYHOOD, BLACK FOLKS, GOOD FOOD, GOOD OLD DAYS, AND THE TELLING OF TALES

A couple of weeks back a question from the accountant who handles my taxes each year started my mind down a ragged rabbit trail of the sort I seem eminently capable of traveling on a regular basis. She asked when my father died. At first blush that inquiry may seem more than a bit strange, but it was in the context of partial ownership of a tract of land he inherited through my mother, who in turn had come into it from her adoptive mother. The story is a terribly complicated one, eventually involving upwards of thirty owners and the unwillingness on the part of those owners to do anything with the land (even harvest a portion of the mature timber on the acreage). Our family had done nothing except pay our portion of taxes on it for decades without seeing any return whatsoever.

My siblings and I finally moved towards partition (in essence, a forced sale), and that too got complicated thanks to a lawyer who did little to move from square one over a period of six years. Finally our complaining, implied threats of reporting him to the state bar, and our outright disgust led him to offer to buy our shares. We sold in a New York minute and I thought it was all behind me until realizing my portion of the modest sum from the sale had to be reported on my taxes. That was what underlay the accountant’s question, and never mind the multiple headaches associated with it, she actually resurrected some warm, winsome memories. One was of my father, who lived to the age of 101 and was bright as a new penny right to the end. Having also sadly seen the tarnished side of the coin, with my late wife’s extended period of dementia, I realize just how much we, as a family, were blessed by Dad’s longevity.

The other thing this train of thought produced was fond recollection of a black woman who died not long after Daddy passed. She had been a housekeeper, helpmate, but most of all a friend to both my parents but especially to my father after Mom’s death. She did cleaning and ironing for him, occasionally baked a black walnut cake for which we eventually discovered Daddy was paying far too little, but most of all eased his loneliness by sitting and chatting after performing her chores every time she came to his house.

That individual, Beulah Sudderth, was one of those rare souls who commanded respect from everyone who knew her. Since I grew up within easy walking distance of where she lived, I got to know her at a young age. She lived in the area known as “Nigger Town,” a term which would never pass political correctness muster in today’s world and may bring the whole “Woke” mob down on my back. Indeed, looking back I guess it was inappropriate in the 1950s, although I would note that blacks used the term with regularity. Yet as a youngster I never really thought of it one way or the other, although I didn’t use the derogatory term and certainly my parents didn’t. For us, we simply recognized the reality that we had blacks as close (and good) neighbors. There weren’t a lot of them—perhaps 150-200 blacks lived in the entire county—and thanks to our house being so close I knew virtually every one of them.

Most were wonderful folks–hard-working, fun-loving, optimistic, impeccably polite, and invariably cheerful—and without any of the highly questionable characteristics displayed by the supposed leaders of the ilk of Jesse Jackson or Al Sharpton. Some of them were among my best friends as a boy. That included those who were roughly my age with whom I played basketball on the outdoor court in our yard on a regular basis. We may not have gone to school together but no one thought twice about our playing together. One of those individuals from those long-gone days of boyhood officiated at Beulah’s funeral service, and some indication of the sort of background that small group of African-Americans had, and what they accomplished, is given by the fact that he holds a Ph. D. in religious studies, is an ordained minister, and has had a stellar career as an academician.

While I did not know Beulah all that well as a youngster, that changed in the final two decades of her life. We became good friends. I made a point of visiting her every time I was back where I grew up, and my admiration for her grew each time we would sit and chat. She had been a caregiver to a whole community, looked after two sisters in their later years, and was one of those wonderful people who never wasted anything. I loved to call her saying I had a mess of trout for her or some vegetables I thought she might use. I did so because her invariable response to my question, “Can you use some trout?” was an enthusiastic “Oh, yes!” Similarly, I loved to hear her say the words “I know” when we were discussing some subject. That phrase is common with young kids, but in the case of Beulah she really did know.

Late in my father’s life I learned that Dad was paying her a mere pittance for the scrumptious black walnut cakes she made for him on a regular basis. I just happened to ask him or her, I don’t remember which one, the payment amount. When I learned it was $10 I asked Dad if he knew what a cake like that would cost from a bakery and told him it would likely be between $30 and $40. Characteristically, his reply was: “If I ate a bite of cake that cost that much it would give me a bad case of indigestion.” I just chuckled to myself and henceforth my brother and I made up the difference between what Dad paid and what he should have been paying. When I first did this Beulah said: “Why, I’d bake that cake for him for nothing.” That wasn’t just talk. She meant it, and that gives some index to the woman and her character.

As lovely in a visual sense as she was as a person (see photo of her above), a couple of years before her death Beulah blessed me with a most meaningful physical reminder of her goodness. It came in the form of a cutting from a flowering cactus somewhat similar to those sometimes known as Christmas cacti. It doesn’t bloom at Christmas but on a schedule of its own I’ve never quite figured out. However, when that happens the results are spectacular, because each bloom is the size of my open hand (see image below).

Whenever I enjoyed a conversation with her, my thoughts would invariably go back to another wonderful black woman, this time one who figured quite prominently in my boyhood, Aunt Mag (Maggie) Williams. As a boy I never knew her last name, although I incorrectly thought it was Parrish. To me she was just Aunt Mag, with the “Aunt” being a title of respect accorded an elderly woman. She and her daughter, Elma, lived just down the road from us, and they were, in terms of material goods, about as poor as it was possible to be. “Poor as Job’s turkey” was the phrase I often heard my parents use to describe them. Yet both Aunt Mag and Elma had a splendid work ethic and in some senses lived a simple existence worthy of envy. According to my parents, they washed my diapers when I was a baby, boiling them in a big iron kettle situated over a fire outdoors. They kept chickens (we sometimes bought eggs from them when they had extra ones) and raised a garden, and Daddy always planted a bit of extra stuff in our garden with them specifically in mind. He loved to talk about how Aunt Mag approached the whole matter of garden produce.

When she noticed an abundance of something like mustard greens, tomatoes, or turnips, she would ask if she could have some. Invariably she did it in a polite fashion, always finishing with the phrase, “I always say it ain’t worth having if you don’t ask for it right.” Whatever they grew, gathered (they didn’t let poke salad, wild strawberries, blackberries, or indeed any of nature’s readily available bounty go to waste) or got from us, Aunt Mag could work sheer culinary magic with it. She cooked on an old cast iron wood-burning stove we had given her when we got “big time” and acquired an electric one. Even today, just thinking of the food which came from Aunt Mag’s stove sets my salivary glands into involuntary overdrive.

She also was decidedly of the “make do with what you’ve got” school of thinking when it came to all matters culinary. I’ll offer two anecdotal examples, both of which tickled my fancy as a boy and continue to do so as a man. Aunt Mag’s chicken lot was a gold mine when it came to digging worms for fishing. A quarter hour with a mattock could produce enough worms for a full day on the creek or river, and it didn’t seem to matter that I dug them day after day in the warm weather months—there were always plenty more. Aunt Mag (and the chickens) welcomed my bait-gathering activities, but the former did expect something in return. Namely, regular messes of fish. Day after day I would bring her a mixed stringer of catfish, panfish, and a member of the stoneroller family locally known as knottyheads. Then came a string of days of fishing when I returned without the normal and expected bounty. Aunt Mag looked at me in abject dismay and asked: “Didn’t you catch any?”

I confessed that the fishing had been slow and that about all I had managed to catch were quite small bluegills which I had turned loose. She put her hands on her hips in what was clearly a posture of exasperation, eyed me quizzically, and asked a further question: “Were they bigger than a butterbean?” I acknowledged that while they were small, they did indeed exceed the size of a butterbean to an appreciable degree. Her response said it all. “Well, I’ll eat a butterbean.”

Aunt Mag also was a regular customer for the carcasses of muskrats produced by my winter trapping, and she paid perfectly good “cash money” for them to the tune of two bits per muskrat. Had my father know of this particular moneymaking enterprise he would have tanned my hide, but I always needed cash for a handful of shotgun shells (you could by them individually in the 1950s, at least where I grew up). Accordingly, I took her money most willingly.

Then there came a bitterly cold winter’s day when school was closed because of snow. I had been out all day, by myself, in pursuit of rabbits, squirrels, a covey or two of quail, and maybe the odd grouse. I don’t remember whether or not I had killed anything, but I stopped by Aunt Mag’s on the way home to warm up a bit but mostly because I knew I could get a head start on whatever Mom might have for supper that evening. Sure enough, when I walked in the door of Aunt Mag’s decrepit but impeccably clean and neat home a wonderful aroma greeted me.

Greedy gut teenager that I was, I asked what was on the stove. Aunt Mag replied, “I’ve done cooked me a stew. Get you a bowl and help yourself.” That was exactly what I had hoped to hear and I dug deeply into the savory mix of vegetables, meat, and gravy which was steaming in the massive Dutch oven she used for a lot of her cooking. Talk about bringing tears of joy to a glass eye—that was provender of a matchless sort. It was so good, in fact, that when invited I joyfully spooned up a second bowl. I noticed, as I ate the stew, helping it along with a big chunk of cornbread, that the meat was of a texture and color I had never experienced.

Finally satiated, I thanked Aunt Mag and inquired as to just what I had been eating. She had been waiting for that moment all along. Cackling like one of her prime hens that had just laid an egg, she showed every tooth in her mouth (there weren’t that many), and said: “Boy, you been eatin’ muskrat.” I should have known but somehow the connection between my trapping and her cooking hadn’t dawned on me. Incidentally, I didn’t tell my father of that experience until long after I was grown, and his response was to shake his head in disbelief and say: “I never thought a son of mine would stoop to eating a rat.” Actually, muskrats are vegetarians, and properly dressed (you need to be sure you remove the scent kernels under their legs) they make mighty fine fixin’s.

Aunt Mag could also cook rabbit and squirrel like nobody’s business, and the baking miracles she could work on that old stove were just that—miracles. Cathead biscuits, cracklin’ cornbread, cakes, pies, cobblers, cookies and more populated that ramshackle old kitchen with a world of goodness. I considered her a dear friend, just as I did Beulah. We could sit and talk about things as diverse as simple gardening pleasures or local gossip.

In the case of Beulah, I also had a living history book on the black folk with whom I had grown up. She would readily say such a man had been “bad to drink” or that a local girl who had gone away, gotten an education, and come back thinking she knew more than anyone else was “an uppity sort who thinks way too highly of herself.” She could talk about the local black baseball team which existed for many years and the celebratory occasions which were connected with their home games, served the same little church faithfully as a member (there were only five left when she died) for eight decades, and was as good a woman as I’ve ever known. I said as much in a short eulogy offered at her funeral service, and as I write this I have a lasting connection with Beulah to console me in the form of the flowering cactus mentioned above. Whenever I walk by it, and especially when I water the plant, an aura of goodness envelops me.

That’s enough rambling, but I’ll close with two thoughts which will probably get me some negative comments. First, I have no use for folks, and it doesn’t matter whether they are black or white, who suck at the government teat, have no concept of a work ethic, or who are strangers to morality and decency. Second, our policies on both the state and national level contribute to this situation of welfare babies, food stamps, subsidized housing, and so much more. Beulah was my kind of person, and it had nothing to do with skin color. She worked hard all her life, was the essence of caring and compassion in all she did, and was one of God’s truly good and gentle souls. I miss her a great deal.

JIM’S DOIN’S

About the time last month’s newsletter went off to my webmaster, I had a welcome and deeply moving visit from a couple of longtime buddies who are fellow laborers in the vineyard of outdoor writing, Pat Robertson and Terry Madewell. I’ve called each of them friends for well over a quarter of a century and have hunting and fished with both of them on multiple occasions. They’ve been solid, productive, successful outdoor communicators even longer than I’ve known them.

The reason for their visit was to deliver something which was deeply meaningful to me—an Asian pear tree. It was a gift from the entire membership of the South Carolina Outdoor Press Association in memory of my late wife, Ann. I can’t think of anything more suitable. She loved Asian pears, was fascinated by anything and everything I grew, and could work culinary wonders with the products of my garden, berry patches, fruit trees, and the like. Now every time I look at the tree it will evoke warm, wonderful memories, and with a bit of good fortune it will be bearing tangible results, in the form of luscious fruit, in just a couple of years (the tree was a good-sized one which the nursery said should meet that time frame).

My writing continues to plug along in pretty much standard fashion. “10 Turkey Hunting Mistakes to Avoid,” in “Sporting Classics Daily,” for March 1, 2021 is one of my fairly regular contributions to that on-line offering (you can subscribe for free at www.sportingclassicsdaily.com). Another one is “Making Tools Out of Turkey” (March 21, 2021) which looks at various items which can be crafted from the inedible portions of a wild turkey.

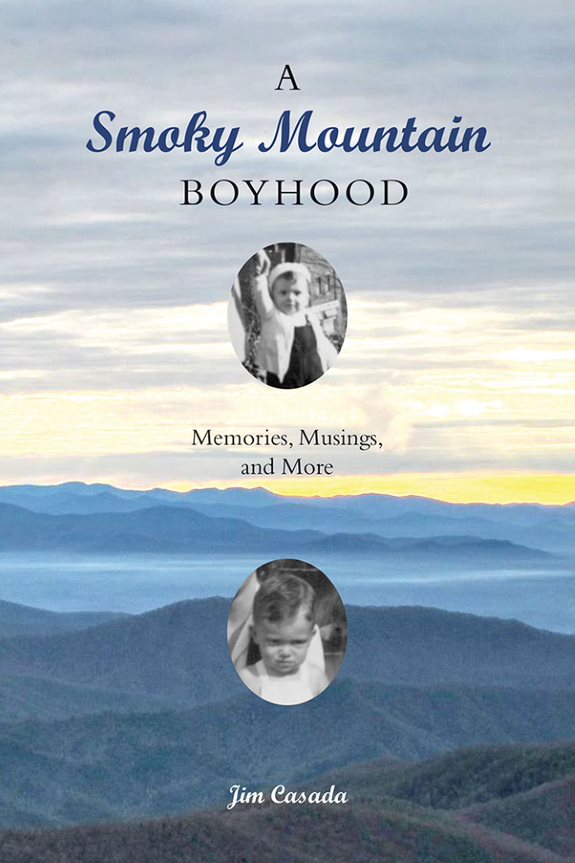

Once in a blue moon or so you get a genuine surprise that is also a delight. That’s not happened to me in recent weeks once but, incredibly, twice. A friend from graduate school days at Vanderbilt a full fifty years ago, David Morton, saw news of my recent book, A Smoky Mountain Boyhood, and reached out to me by e-mail. We had great fun catching up on one another’s lives and to my considerable delight he informed me that the better part of thirty years ago he wrote a biography of DeFord Bailey, the great black harmonica player who appeared on the very first Grand Old Opry and who eventually became a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame. I found some Bailey recordings on YouTube and when he turns loose on one of them, “Dixie Flyer Blues,” you’ll catch yourself looking around to see if you are standing on the railroad tracks and watching for the train.

The second development although it goes back a mere forty years rather than fifty, was a phone call from a fellow from Ecuador, Guido Paez, I coached in soccer during my days at Winthrop. He was a fine player who got everything out of his skill set and then some along with being an intensely likeable individual. I always sensed that Guido came from an influential family, but I had no idea of the prominent figure he would become in the world of Ecuadorian business until I did some checking on him. It was gratifying, as it always is, to see someone who you watched mature and perhaps influenced in some small fashion succeed in life. For all of his considerable success as a business figure in his native country, what most impressed me about his achievements was that a few years back, when his wife suffered a massive stroke from which she was given only a six percent chance of survival, he abandoned everything for her. Thanks to his loving and unstinting care she has almost fully recovered and can once more enjoy life. Simply put, I’m proud of him, as I am of so many former players who have become fine men and fine citizens of the world in which we all live.

Finally, there’s some wonderful news, at least for me, on the book front. I just signed a contract with the University of Georgia Press for my next book. It will be a sort of companion volume to A Smoky Mountain Boyhood (if you haven’t already acquired a copy, and I’m grateful to the many of you who have done so, I’ve got plenty of copies available) and the subtitle is “A Smokies Food Memoir.” We’re still debating the main title, but I’ll provide appreciably more information next month. Meanwhile, I wanted to share the news and note that up to this point the experience of working with the University of Georgia Press folks has been an exercise in pure delight.

*********************************************************************************

RECENT READING

I’ve been on a Wilbur Smith binge in the last few weeks, re-reading some of his splendid novels set in Africa and enjoying others for the first time. He’s a consistently first-rate writer and I especially appreciate his meticulous detail when it comes to getting the factual underpinnings of his works of fiction right. So many authors fail to do that and when I’m familiar with the subject matter that’s an immediate “turn off” for me. Incidentally, if you want to sample some of Smith’s work (I think he is almost in a class by himself when it comes to adventure novels with an African setting), I’ve got an extensive lists of his books available on my website. Many of them are bargain priced.

My other recent reading has focused on Appalachian literature. It has included some scholarly items such as Richard Starnes, Creating the Land of the Sky and dipping into the mammoth collection, Horace Kephart Writings (edited by Mae Claxton and George Frizzell), for which I contributed the introductory coverage for the section on his writings on firearms. On the lighter side, a reader of this newsletter very graciously introduced me to the fishing-based novels of Victoria Houston and generously shared two of them, Dead Angler and Dead Creek. Then I’ve done considerable delving into cookbooks, partly in connection with work on the food memoir mentioned above but also because I enjoy culinary works which include considerable narrative material. My reading has included Ruth Reichl, Tender at the Bone: Growing Up at the Table, several highly useful little cookbooks by Patricia Mitchell covering subjects of particular interest to me, and works by noted food writer Ronni Lundy including Shuck Beans, Stack Cakes, and Honest Fried Chicken and Sorghum’s Savor. She’s good and knows how to tell a story along with sharing fine recipes. Speaking of recipes, let’s conclude, as I always do, with a few offerings.

APRIL FIXIN’S

When I think of April and food, multiple things come to mind. Foremost among them are the various ways of preparing eggs (always something to be addressed after the extravaganza of Easter egg hunts and chickens which went into laying overdrive this time of year), the first wild vegetables of a mountain spring such as ramps and poke salad, and trout fresh from a mountain stream.

GARDEN OMELET

Come spring’s greening-up time, some ancient switch of procreation is triggered not only in chickens but most birds. Laying hens are at their most productive in this season, and that translates to eggs aplenty for anyone raising chickens. Eggs are also one of the less expensive protein sources in grocery stores, and a super-abundance of eggs is a pleasure, not a problem. Sometimes described as the perfect food, and a grand way to enjoy them, simple as it scrumptious, is in a two- or three-egg omelet incorporating whatever is available in the way of vegetables from my garden or that of nature.

Vegetable choices might involve asparagus, spring onions, ramps, spinach, Swiss chard, morel mushrooms, water cress, or other items. Add salt and pepper to taste, some sharp cheese, a bit of butter, or maybe crumble in a couple of slices of bacon or streaked meat fried to a crisp and you have some mighty fine eating. Omelet pans are great, but you can make an omelet in a large frying pan. Just empty the beaten eggs and other ingredients into a large, well-greased skillet, and once the bottom is firmly cooked, flip half over to make a half-moon shape and complete cooking. HINT: Adding a tablespoon or so of warm water to the mix when you beat the eggs up produces a fluffier end product.

CHICKEN AND EGG SALAD

This is a fine way to utilize left-over stewed or bake chicken and/or a surplus of eggs. It’s good whether eaten atop a lettuce base, with soda crackers, or in a sandwich.

2 cups chopped chicken (or use blender to pulse it to a coarse but not overly minced state)

4 large eggs, boiled, peeled, and coarsely chopped

¼ cup chopped sweet pickles

Salt and black pepper to taste

2-3 tablespoons of mayonnaise (more if needed for right consistency)

1-2 tablespoons of prepared mustard (amount will depend on how much you like mustard’s tang)

Prepare the chicken, eggs, and pickles then place together in a large mixing bowl. Add the mayonnaise, mustard, salt, and pepper. Stir thoroughly with a large wooden spoon. Refrigerate until ready to eat.

POKE SALLET WITH EGGS AND BACON

Among the first “pot herbs” to become available in the spring, thanks to having exceptionally high levels of vitamin A poke needs to be cooked three times before serving. Also, only the new growth, when it is three or four inches tall, should be used. After washing the greens, place in a sauce pan and bring to a rapid boil and continue for 20 minutes. Repeat the process twice more, draining and starting with cold water. While cooking the poke, fry several strips of bacon (or streaked meat) until crisp and save the drippings. When boiling of the poke greens has been completed, add the drippings and cook in the pan in which the bacon was fried. Top with crumbled bacon and thin slices of hard-boiled eggs. Proper preparation of poke sallet takes time, but as one of the earliest greens of spring the effort is well worthwhile.

PAN-FRIED TROUT

2 to 3 small trout (6 to 8 inches length is ideal—they are tastier than larger ones) per person, dressed

Stone-ground cornmeal

Salt and pepper

Bacon grease or lard

Clean the fish and leave damp so they will hold plenty of corn meal. Put your cornmeal in a Zip-lok bag, add the trout, along with salt and pepper, and shake thoroughly. Make sure the inside body cavity gets a coating of corn meal. Cook strips of bacon or streaked meat and save grease, setting the meat aside to mix with a green salad or to crumble into fried potatoes. Place the trout in a large frying pan (a cast-iron spider works wonders but modern non-stick kitchen ware is quite suitable) holding piping hot grease. Cook, turning only once, until golden brown. You can help the process along by using a spatula or tilting the pan a bit to splash grease into the open body cavities. Place cooked fish atop paper towels, pat gently to remove any excess grease, and dig in. If it is springtime, serve with a backwoods “kilt” salad (branch lettuce, ramps, and bacon bits with leftover hot cooking grease poured over it for a dressing), fried potatoes and onions with bacon bits added, and something for the sweet tooth to finish.