November 2012 Newsletter

Click here to view this newsletter in a .pdf with a white background for easy printing.

Enough of that though, and if I’ve created a bit of angst I’ll simply note that no one ever accused me of being overly given to either political correctness or possessing a polished sense of diplomatic demeanor. Let’s turn to some thoughts about suitable gifts for Christmas. Anyone who knows much at all about me realizes I am and always have been an inveterate reader. I average consuming about five books a week, thanks to a lifelong habit of reading at bedtime and the fact I am blessed with the ability to read quite rapidly. Maybe that explains in part why I became a writer as well as offering an underlying reason for my having done a great deal to resurrect great sporting literature from the past which had somehow been forgotten or become obscure with the passage of years. I still have the first two books I ever received at Christmas, both of them given to me by my mother. She somehow realized just how much I loved to read, and she had a real sense of what appealed to me. Those books, incidentally, are Zane Grey’s Spirit of the Border and an early edition of Horace Kephart’s Our Southern Highlanders which Mom had rebound for me. I might add that there is a great deal about Kephart I admire such as his knowledge of firearms and his unrivalled abilities as a woodsman and camp cook, but there is also a great deal about him which evokes nothing but disdain from me. He was in many ways a miserable human being, a man who abandoned a wife and six small children and who fought Demon Rum, without anything approaching full success, all of his adult years. He came to the Smokies dead drunk and left them in pretty much the same state. Moreover, Kephart’s stereotyping of the mountain folks from whom I am descended, and I’m immensely proud of my roots, is a flat-out travesty. I’ve said as much in print many times over the years, and I have solid and substantial evidence, not the least of it Kephart’s own words, to support my strongly-held feelings that many of the chapters in his best-known book are nothing less than a travesty. His descendants hold otherwise and pretty clearly have no use whatsoever for me, with one great-granddaughter having gone so far as to launch an abortive campaign to get me fired as a columnist for the Smoky Mountain Times, the little weekly newspaper in Bryson City, NC, where I grew up. I’m happy to report, thanks in no small measure to lots of loyal readers, that the effort failed. That’s another bit of wandering, something I’m inclined to do, but it all ties in to the fact I love books as well as being a person who doesn’t hesitate to speak his mind. Book are gifts that last, and for me they have been a comfort, sources of ongoing pleasure, and a means of self-education in the world of the outdoors. Second only to “being there,” books are good friends which take the reader to realms of wonder. With that in mind, I’m simply going to list a wide-ranging selection of books I have written or edited and which I have in stock. Orders over $100 qualify for a five percent discount and free shipping (insurance, if desired, is extra); orders over $200 qualify for a ten percent discount and free shipping. As always, I am glad to sign, inscribe, and personalize books as per your wishes. Remember to include 7 percent tax if you are a resident of South Carolina. Here’s the SPECIAL OF THE MONTH along with a wide-ranging opportunity to fill some slots of your Christmas gift list.

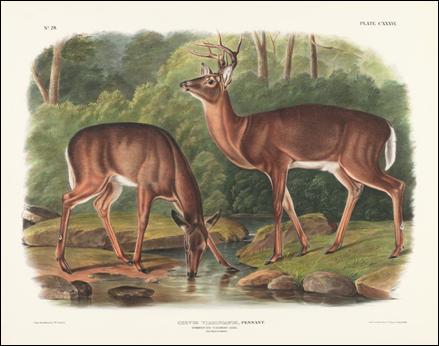

Prior to commencing the narrative portion of this month’s newsletter, I thought it might be advisable to go back and read some of what I’ve written in previous November offerings. Since my first newsletter appeared in September, 2004, that translates to this being the ninth time I have shared some ruminations and recollections about the month. Those of you who are familiar with Robert Ruark, and if you aren’t do yourself a big favor and make a point of reading him (in my studied opinion his book, The Old Man and the Boy, is the single finest piece of outdoor literature ever written), probably realize that he loved November. Indeed, one of his timeless “Old Man” stories carries the title, “November Was Always Best.” Similarly, Havilah Babcock, a wonderfully talented writer who was an English professor at the University of South Carolina, entitled one of his collections of tight, sprightly written essays My Health Is Better in November. While I don’t quite concur with the pride of place they accord November, I can’t argue with it a whole lot either. The reason for their respective choices was simply. Both were avid bird hunters. For the uninitiated, “bird” in this part of the world refers to bobwhite quail. Sadly, and it is a decline as great in its way as is the comeback stories associated with wild turkeys and white-tailed deer, the glorious little package of six ounces of feathered dynamite is and long has been in abject decline. This isn’t the place to go into all the many reasons for the disappearance of this delightful little patrician of peafield corners and broom sedge covers, but bird populations are but a wispy shadow of what they were in my boyhood. I was an adolescent at the tail end of the quail’s golden era, and even in the Smokies where I grew up, not a geographical location one would consider an ideal setting for whopping bevies of birds, they were plentiful. Typically we would flush anywhere from a couple of coveys to half a dozen or more in a day’s rabbit-hunting outing. My uncle, who owned big, rangy pointers and hunted birds with a will, frequently found upwards of a dozen coveys a day. Yet even then, in the 1950s, bird numbers were dwindling in alarming fashion. I can recall old timers musing about “Mexican quail” and complaining that the “good old days are gone.” They were wrong about the former but right on target in regard to the latter. My brother, who is a decade younger than me but enjoyed a strikingly similar boyhood in terms of exposure to sport, recalls appreciably fewer quail than was my experience. The same was true with cottontails, and that should come as no surprise. The two game species share common habitat preferences and where one thrives the other is likely to do so as well (or at least that was once the case—in many areas quail are completely gone). That’s a rather long-winded side trip down what might be styled, in keeping with the subject matter, a literary rabbit trail, but there’s a reason for it which transcends personal experience. It is my studied opinion that when it comes to fine literary output, no single game species, small or large, has produced finer tales than the noble quail. Among the giants of outdoor letters who have sung its praises are not only Ruark and Babcock, but Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Charlie Elliott, Charles Dickey, and a whole host of others. Moreover, one of the most gifted of all America’s wildlife biologists, both in terms of what he accomplished from a scientific perspective and his gifts as a writer, Herbert L. Stoddard, is best remembered in connection with his work on quail. In other words, when I think of Novembers past or start musing about the literature of fall sport, quail invariably figure in the picture. Mind you, I didn’t kill all that many of them as a boy. The first gun I owned, and it was my primary hunting tool right through high school and on through college, was a single-shot Stevens Model 220A 20 gauge. It was choked tighter than a miser’s purse. That made it a mighty fine tool for hunting squirrels, but hitting a quail with it, or for that matter a woodcock, running rabbit, dove, or grouse, was highly problematic. That consideration notwithstanding, rest assured that any time I flushed a covey in season, whether out rabbit hunting or when alone on an old-fashioned mixed bag hunt (something I did a great deal of in my boyhood), I filled the air with a load of Number 6s. Once in a while Lady Luck would take pity on me and my efforts would be rewarded. Quail also figured prominently in what must be reckoned as one of the most poignant and powerful experiences of my entire hunting career. My wife was an only child; I think I can say with complete honesty that her parents, and especially her mother, considered that she had married so far beneath herself as to be dredging the uttermost bottom of the marital pool. Or, to put matters another way, to say that her mother viewed me in a manner which ranged between disdain and abject dismay might well be understating the case. Some of that attitude rubbed off on my father-in-law, although he was a gentle, easygoing fellow who seldom wore his emotions on his sleeve. Thankfully, his perspective on me underwent a major revision one Thanksgiving when I was in graduate school. We were spending the holiday with Ann’s parents (with the idea being we would spend the longer Christmas one with my mother and father), and the opportunity for a quail hunt presented itself. A family friend had a fine pointer, a big farm, and reportedly, plenty of birds. Accordingly, the day after Thanksgiving found us afield about 9:00 a.m., with the sparkling frost from a chilly morning just beginning to melt atop golden fields of broom sedge. What an outing it was! There were quail everywhere, and that bony old meat dog, not overly long on style but absolutely full of savvy and with a nose that was a gift from the bird-hunting gods, made one covey find after another. My father-in-law, a gentleman sportsman to the core, gave me the first shot on every covey rise. Mind you, my personal scattergun armory still consisted solely of that little 20 gauge, so once I pulled the trigger there were plenty of options left for him and his old humpback Browning. He was a helluva wingshot, and most every covey rise found him putting two and sometimes three birds down. At day’s end we had two limits (24 birds), and at most I might have accounted for a quarter of that total. What really counted, however, was the fact that each of us came to see the other through decidedly different eyes. Never mind my indifferent wingshooting, he realized I was a sportsman to the core and that I had spent my fair share of time, and then some, in the outdoors. For my part, I broke through a barrier which had really been erected by my mother-in-law, not him, and from that point forward until his death (sadly, it came just a few years later) our relationship was much warmer and filled with an ample amount of mutual respect. Hunting had created a bond, a commonality, which otherwise almost certainly would never have emerged. It is one of my fondest recollections of November. Another cherished memory revolves around the dogs, all of them beagles, which loomed large in my boyhood days. Daddy always had rabbit dogs, usually two or three but sometimes a good many more when a bitch had had a litter, and as is likely to happen with a boy who thoroughly enjoyed being by himself (I’ve always had a tad of a misanthropic streak about me), I developed great fondness for those canine companions. I still recall a cold day in late November when I ventured out alone with Lead and Lady, the first pair of beagles I really remember. It was one of those adolescent outings which, while never finding me more than two or three miles from home, took on all the characteristics of a grand adventure in my mind. I had a hand-me-down Duxbak coat stuffed with food left over from Thanksgiving, a pocket full of shotgun shells, staunch dogs at my side, and my trusty little 20 gauge. The mountain world was my oyster, and what a day it was. By the time I headed home in the gloaming, footsore, weary, and wonderfully satisfied, the food which had filled that old Duxbak coat at dawn had been replaced by a bulging game bag. I had killed two squirrels, three rabbits, and a grouse. That may not seem impressive to many (or any) of you, but rest assured I was proud as punch and thought of myself as a mighty hunter who was a master at putting meat on the table. There are other warm and winsome memories almost without number. Family Thanksgiving gatherings where an abundance of fine food and finer fellowship held sway rank high among them. Some of the dishes from those celebratory feasts are still part of family tradition today, with chestnut dressing being at the top of the list. I have no idea where the recipe originated—probably with Grandma Casada in the days when that giant of the eastern forests, the American chestnut, still reigned supreme—but it wasn’t Thanksgiving without cornbread dressing chock full of chestnut pieces. We still eat it and every bite, liberally laced with giblet gravy, takes my mind back in time. It’s just that we use Chinese chestnuts from trees in my yard rather than true American chestnuts. Try chestnuts with your favorite dressing or consult the recipe referenced below. I think you’ll be pleased. Then there was Aunt Emma’s ambrosia, Grandma Minnie’s stack cakes featuring sauce made from dried apples, Mom’s apple and black walnut cakes (she always made a bunch and we feasted on them for Thanksgiving and again in the Christmas season), watermelon rind pickles and pickled peaches, pumpkin chiffon pies (Ann still makes these at Thanksgiving), and of course turkey with plenty of vegetables. Or, to put matters more accurately, sometimes there was turkey and sometimes there would be two or three baked chickens. I actually liked the chicken better than the turkey and as long as Grandma and Grandpa raised chickens they were what we had. Only when they had reached an age and state of declining health which meant giving up the chickens and the raising of hogs did the family make the transition to turkey. Speaking of hogs, November was also hog-killing time. That lasted until I was 12 years old or thereabouts. Grandpa Joe fell and shattered his hip while out squirrel hunting one year, and I’m pretty sure that was the last time the family raised, butchered, canned, and cured its own pork. It was quite an undertaking, with several properly fattened hogs being butchered in a single day. It was an incredibly full day of work—Grandpa killing the hogs at daylight on a cold morning, the men folks carefully gutting them, and then everyone pitching in on the skinning, rendering of the lard, cutting and working up the meat, and all the myriad of chores associated with hog killing. I’m was part of the process, although in all honesty what I remember best are the end products—fresh tenderloin, backbones-and-ribs cooked so you could gnaw the ribs and suck the marrow out of them, crackling cornbread, delicate pieces of country ham accompanied by redeye gravy, vegetables cooked with streaked meat, and more. Pork was the main meat for mountain folks in those days. It’s funny how food memories loom so large as I look back, taking second place only to those of hunting and fishing. Maybe that helps explain why I’ve always loved to eat and why my wife and I have written a bunch of cookbooks. At any rate, I know I’ve been blessed to understand the cycle of life in terms of realizing meat isn’t just something which magically shows up on the shelves of grocery stores. I’ve seen it, both in terms of wild game and in things we raised, from the beginning of the process to the end. Every child should have a similar opportunity, because I genuinely believe it will give them a fuller, better perspective on life. Recently Read / Recommend One other November pleasure was indulging in reading, the perfect recreation for nasty, rainy days and nights when I tired of listening to the Grand Old Opry on WSM out of Nashville or the Wayne Raney show on WCKY in Cincinnati, Ohio. Along those lines, I thought I’d start adding a new feature to the newsletter, and please share with me your thoughts on it. If there’s sufficient positive reaction I’ll make it a regular part of these offerings. It will come in the form of commenting on things I’ve recently read and/or books I recommend. Although I read a lot of fiction, I plan to stick strictly with mention of nonfiction in the form of biographies, autobiographies, and works on various aspects of the outdoor experience. Here’s a sample of what I’ve read in the last month or two, along with a couple of books I figure everyone who loves the outdoors ought to sample and savor. Those with an asterisk beside the author’s name are books I particularly recommend. *Robert Ruark, The Old Man and the Boy. I reread this masterpiece every year. *Gene Hill, Mostly Tailfeathers. Charlie Elliott, An Outdoor Life. Elliott’s autobiography—it is difficult to find. *Ken Morgan, Turkey Hunting—A One Man Game. Andrew Vietze, Becoming Teddy Roosevelt. Horace Kephart, Mountain Magic. *Alston Chase, Playing God in Yellowstone: The Destruction of America’s First National Park. A scathing indictment of officialdom and its seemingly endless capacity to screw up. Mindful of bureaucratic bungling of major proportions currently taking place in my beloved Great Smoky Mountains National Park, this is a cautionary tale for anyone who cherishes wild places. Betty Keller, Black Wolf: The Life of Ernest Thompson Seton. Peter Clarke, Mr. Churchill’s Profession. On Winston S. Churchill as a writer. RECIPES CHESTNUT DRESSING Go to the newsletter archives for November 2009, and you’ll find this recipe. BAKED FLOUNDER WITH PARMESAN SOUR CREAM

4 flounder fillets Arrange the fillets in a single layer in a lightly greased 9x13-inch baking dish. Combine the sour cream, ¼ cu cheese, paprika and salt in a medium bowl. Spread the sour cream mixture evenly over the fillets. Layer the bread crumbs and butter over the fillets. Sprinkle two tablespoons cheese over the bread crumbs. Bake at 350 degrees for 25 minutes or until the fish flakes easily. OYSTER STEW

2 (12-ounc) cans oysters or the equivalent of fresh ones you’ve shucked Drain the oyster, checking for pieces of broken shell. Sauté the onions in the olive oil in a Dutch oven over medium-high heat. Add the flour, whisking until blended. Add the oyster and stir to combine. Stir in the milk, parsley, garlic salt, and pepper. Bring to a boil and remove from the heat. Serve immediately with oyster crackers or saltines. VENISON LONDON BROIL

¼ cup canola oil Combine the oil, lemon juice, soy sauce, sugar, and garlic in a bowl and whisk to combine. Pour over the steak in a glass baking dish or plastic bowl. Cover and refrigerate for four to eight hours, turning occasionally. Prepare the grill for direct medium heat and oil the grate. Drain the steak and discard the marinade. Grill the steak to desired doneness, turning once (12 to 14 minutes total—do not overcook). Let stand for five minutes, then slice thinly across the grain. Thank you for subscribing to the

Jim Casada Outdoors

newsletter. |

|||||

|

Send mail to

webmaster@jimcasadaoutdoors.com with

questions or comments about this Web site. |

Jim Casada (Editor), Carolina Christmas: Archibald Rutledge’s

Enduring Holiday Stories. Hardbound.

Jim Casada (Editor), Carolina Christmas: Archibald Rutledge’s

Enduring Holiday Stories. Hardbound.