Jim Casada Outdoors March 2016 Newsleter

Click here to view this newsletter in a .pdf with a white background for easy printing. The Great Spring Book Sale With turkey hunting season at hand, a time which I annually await with great eagerness and, six weeks or so later bid a fond farewell after daily pre-dawn risings, long hours in the woods, haunted dreams of elusive gobblers, and general sleep deprivation, I’ve decided to do some stock reduction in my extensive holdings of books on the subject. A whole host of authors and titles, more than two dozen in all, appear below. Each book is reduced well below what I have it listed for on my Web site. Better still, buy any five and the sixth one is free, or if you want a running start on a turkey library, I’ll send a copy of all 25 books for $200 (they total $283). Postage and shipping are extra at $5 for one book, $7.50 for two, and $10 total for three or more.

PLEASE NOTE THAT THIS OFFER IS GOOD ONLY THROUGH MAY 15

TO ORDER, CALL OR E-MAIL Tel.: 803-329-4354

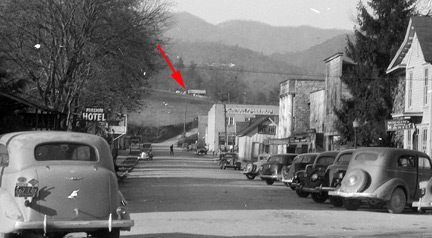

Jim's Doings Other than working away at various assignments and longer range projects, my life of late has been pretty humdrum. Frequent visits to the memory care facility where my wife is located (each one of them ever so sad), some experiments in the kitchen trying new dishes, and doing my level best to get in at least 10,000 steps a day to meet the demands of a dandy Fitbit device my daughter gave me for Christmas. That will change in the coming weeks with what I hope will be lots of turkey hunting, including a trip to upper east Tennessee to hunt with two fine buddies whose company I thoroughly enjoy. While there I’ll also be participating in homecoming festivities at the small liberal arts institution where I did my undergraduate work (King University in Bristol) and attending a meeting of the Alumni Advisory Committee of which I am a member. Prior to that I’ll be in Florida fairly briefly for the mid-year meeting of the Southeastern Outdoor Press Association’s board of directors, which I chair. Then in early May I’ll head up to my beloved Smokies to spend a bit of time at my boyhood home (now owned by my brother and his wife). While there I’ll be giving a talk to the Swain County Genealogical Society on the evening of May 5. If you live in the area I’d love to have you attend, and the price (free) is unbeatable. By that time I’ll no doubt be thoroughly worn out from turkey hunting, but that kind of exhaustion is priceless. March for me means getting ready for turkey season ... ... thinking of the morels that will soon be popping up, planting my early garden (I worked with the tiller just yesterday and plan to buy seed potatoes, onion sets, and broccoli and cabbage plants today), and rejoicing in earth’s reawakening. Since reader reception to last month’s offering, a truncated version of a profile of my paternal grandfather which is intended, in slightly fuller and revised form, to be a chapter in my upcoming book, Portals of Paradise: Profiles of Mountain Characters, was so positive, I thought I’d share another profile. This one features a wonderful old black lady who loomed large in my youth. I’m also happy to report that my proposal for the book has been accepted by the University of South Carolina Press, and we are presently dickering on contractual details. They want a finished manuscript by early autumn, which means I need to kick whatever excuse for a muse I have into high gear. If I meet that deadline the book should appear sometime in 2017. I’ve already got a number of you on a “notify when published” list, and if anyone would like to be added to that list, just drop me an e-mail. With that shameless promotion now out of the way (I am trying to make a living of sorts writing, hence this newsletter, the monthly special offerings, and the pitches on forthcoming publications), let’s turn to magical memories of Aunt Mag. I will give an advance warning that if you are prone to mindless political correctness or object to describing the reality of life a half century and more ago as I knew it, then possibly a bit of what follows will offend you. I don’t want that to happen, but nonetheless, I’m determined to describe settings, situations, and society as I knew it as a boy with as much accuracy as possible. I would also note that I thought the world of Aunt Mag, and hopefully some of that admiration will shine through. Maggie “Aunt Mag” Williams (1863-1961) There has never been a sizeable African-American population in the Smokies where I grew up, and anecdotal evidence suggests that it may actually have decreased in the last half century. Certainly such is the case in my highland homeland of Swain County, North Carolina. A few years back a wonderful black woman who had been a dear friend of our family and who was a walking encyclopedia of local history, Beulah Suddereth, told me that the membership rolls of her beloved Morning Star Baptist Church, once a thriving congregation and religious pillar of the local community, had dwindled to five individuals. Details of black history in the region are sparse and folks such as Suddereth with rich recollections and a deep devotion to oral history are mostly gone. Recognition of my dereliction in failing to obtain more information from Suddereth and others shames me, and it also offers a cautionary note to all of us in terms of preserving the past. The profile that follows is one small effort to do so in connection with the African-American presence in the Smokies. Blacks loomed large in my youth, at least in part because of the close proximity of our family home to what was then universally known as “Nigger Town.” It wasn’t really a town at all, just a small section of Bryson City, and grating though the politically incorrect description may seem today, it was readily accepted, among blacks as well as whites, in the 1950s. I played with black youngsters, knew virtually every African-American in the county by name, and the family who lived next door to us had a wonderful black maid who pulled my brother out of their little goldfish pond on multiple occasions. Of all the blacks who figured prominently in my youth though, the one who was the most important was an elderly woman I simply knew as Aunt Mag. An anonymous reviewer of the manuscript in which this profile is to appear took great umbrage with my calling her “Aunt,” suggesting it smacked of racism and condescension regardless of whether or not everyone used the term. My response to the publishing committee was a passionate one—perhaps overall so. I pointed out in somewhat heated fashion that I wasn’t interested in current political correctness being misapplied to personages of a half century ago. Then I noted that far from being demeaning, the usage of aunt was an honorific. Indeed, another greatly admired local woman who was a near contemporary of Aunt Mag’s was Aunt Jennie Cooper. Aunt Jennie was white and the proprietress of a regionally famous boarding house. In the eyes of locals, both were held in high esteem, and earned the term aunt because of their nature, not their race. Aunt Mag was born in the midst of the Civil War, grew up during Reconstruction, and experienced little but hard times all her years. Yet she was one of the most gracious and giving individuals I’ve ever been privileged to know. She possessed the sort of work ethic you seldom encounter today, and her love for life, simple and hardscrabble though hers may have been, was of soul-searing quality. My parents thought the world of Aunt Mag and regularly did things to help her and her daughter, Elma, in what was an ongoing struggle just to survive. Sadly, most biographical details on the wonderful old lady have vanished like milkweed spores driven by a winter wind. I never knew her last name while she was alive, and until presently her gravesite has no marking other than a battered funeral home plaque made of tin placed alongside a small piece of granite (I’m in the process of rectifying that sad situation).

How I would love to know more of her background, and times without number I have retrospectively condemned my free-spirited and foolhardy shortsightedness, something so characteristic of adolescence, for not having talked more with her about her life. Although it would be a pure joy to learn more of the essential biographical details of Aunt Mag’s life, that is an opportunity almost certainly lost for all time. Even older local blacks barely remember her, if at all. The best that can be done, poor substitute though it may be, is to share some reflections of my personal interactions with her and call back fond recollections of our times together. If nothing else, hopefully they will suffice to open a small window into the soul of this humble yet noble human being. Her nature and approach to life typify those of a number of other black matrons whose lives were sprinkled, to borrow from the title of Lorraine Hansberry’s delightful play, like raisins in the sun of my boyhood. Marvelous cooks, mistresses of the “make do” approach to life, pillars of faith, matriarchs of extended families, and what mountain folks of that era aptly describe as “just good people,” they were admired by all who knew them. Aunt Mag was already an elderly woman when I first remember her, and she had an impact on my life almost literally from the day I was born. She lived little more than a stone’s throw from our home, and according to my parents, washed my diapers when I was a baby. That was in the days when convenient disposable diapers were unknown, and our family did not own a washing machine, one of the old wringer type, until well on into my boyhood. Aunt Mag accomplished her diaper washing duties, not only for me but subsequently my siblings, while working outdoors. She had a huge cast iron pot underneath which she built a fire using sawmill scraps from Carolina Wood Turning Company, the place where my father worked. She washed diapers and other items by beating soiled clothing with a stout hickory stick bleached white by constant use and then stirring them vigorously in the hot, soapy water before rinsing in a wash tub. The cleaned diapers and other clothing were then dried on wire clothes lines suspended between trees. In inclement weather she hung them in her house.

I never fully understood the precise relationship between my parents and Aunt Mag, but clearly it involved components of neighborliness, compassion, and mutual admiration. Daddy loved his interaction with Aunt Mag when fall rolled around every year. We had a small apple orchard on the hillside below our house, and most years it produced far more apples than we needed. Aunt Mag had first dibs on any surplus, and she would dry and can them for the winter. Similarly, come fall Daddy always planted a much bigger crop of turnips and mustard greens than we could possibly consume, knowing that Aunt Mag would make her way up the hill, talk a bit to him or Momma, and eventually ask if she could pick “a mess of them fine greens.” This always tickled my parents, because her request invariably concluded with the phrase: “I’ve always said if something ain’t worth asking for it ain’t worth having.” Aunt Mag’s one-acre home place, which she owned, featured a privy, sprawling chicken lot, and four-room clapboard house situated beneath a large white oak. The house had no insulation and on a cold winter’s day you wanted to be as close as possible to the wood-burning kitchen stove which did double duty as the dwelling’s heat source. That stove was a hand-me-down form my parents when they upgraded to an electric one, and daily atop it Aunt Mag wrought culinary wonders. Once I discovered Aunt Mag’s wizardry as a cook, I visited her home at every opportunity, and on more than one occasion slipping off to sample and savor whatever she had available to eat got me into trouble. Yet who could resist a delightful old woman who always had soup or stew simmering atop her stove, with delectable aromas wafting through the house? Or the temptation of fluffy cathead biscuits ready to be adorned with homemade jelly, or maybe a big chunk of cracklin’ cornbread slathered with butter? Such delectables were sure to draw serious attention from a greedy-gut boy. As a youngster it never occurred to me that Aunt Mag was poor as Job’s turkey, although the dots were there to be connected. Every spring I sold her big #8 grocery bags stuffed with poke salad for a dime a bag (what she laughingly called a “poke of poke,” since in Smoky Mountain English a “poke” is a paper bag as well as a wild vegetable). Looking back, I suspect the ten cents was a bit of a budgetary strain, never mind that my going rate for a poke of poke was a quarter. Aunt Mag often paid with two nickels or a nickel and five pennies, and invariably she did so with the admonition, “now boy, you use that money wisely.” With the possible exception of my mother, Aunt Mag loved to eat fish more than anyone I’ve ever known. Both of them considered a platter of fish dressed up in golden brown cornmeal dinner jackets, flanked by dishes of fried potatoes, slaw, and hush puppies (or in Mom’s case, cornbread), about as close to culinary heaven as anyone needed to be while still dwelling on earth. By happy chance Aunt Mag’s chicken lot was pure paradise for fishing worms. A quarter hour with a mattock spent in the shady area where she watered what she styled “yard birds” would produce enough worms for a couple of days fishing. She was quite happy for me to “farm” her worm garden, and when I finished her chickens had a field day with the leavings in the broken soil. We had an unspoken yet mutually understood compact that some of the fish I caught with those worms would end up being given to Aunt Mag. She was quite happy to clean them, though more often than not I took care of that chore. The nature of the catch didn’t matter a great deal. She seemed equally happy with a stringer of knotty heads from lower Deep Creek, a bunch of catfish from the nearby waters of theTuckasegee, or on an increasingly frequent basis as my fly-fishing skills improved, trout. The latter weren’t caught on worms, and Mom insisted on right of first refusal when it came to them. Still, any time there were two or three days in a row when I brought home a limit of ten trout, Momma would say: “Since you’ve been having a lot of luck, why don’t you carry a mess of trout down to Aunt Mag. You know how she loves them.” So things went, summer after summer, from the time I began fishing in earnest, around the age of 10 or 11 and was allowed to venture out on my own, until I headed off to college in 1960. Aunt Mag, worms, and fish were an integral part of my boyhood summers. Seldom did a span of more than three days pass when I didn’t present her with a mess of fish, and she was as consistently grateful for my offerings as I was pleased with endless idle hours spent on streams and the river bank catching them. On one memorable occasion, however, there was an unfortunate break in what had become established ritual. I dug worms in Aunt Mag’s chicken lot for three days running but failed to deliver any fish during that period. The fourth time I showed up she wandered out to the chicken lot, chatted a bit about the weather, and then politely inquired: “Have you not been catching any lately?” I allowed as how I had actually caught a bunch earlier that day, but since all of them had been quite small bream they had been released. She looked at me in a perplexed fashion tinctured by a hint of dismay and asked: “Were they bigger than a butter bean?” I acknowledge that, while small, the bream were indeed appreciably larger than that. “Well,” Aunt Mag said, “I’ll eat a butter bean.” Her message had been delivered in a clear and clever fashion. If a fish was big enough to bite a hook baited with one of her worms, it was big enough for me to keep and for her to eat. I never again made the mistake of practicing catch-and-release when Aunt Mag was part of the equation. She was a committed believer in release to grease. Similar warmth infuses my soul when it comes to recollections of my links to Aunt Mag connected with trapping. A few years after I first began digging worms in Aunt Mag’s chicken lot, a new outdoor pursuit caught my fancy. Intrigued by the skins of ‘coons and muskrats hanging on the outside walls of a shack of an old fellow who lived not too far from us, I began to do some trapping. Although my skills were minimal, I caught muskrats with some regularity along with the occasional ‘coon. Prime muskrat pelts were worth $3 or a bit more in the mid-1950s, and that was big money for a boy whose allowance was a quarter a week. When I discovered Aunt Mag would pay what she termed “cash money” for the muskrat carcasses, I was sure enough in high cotton. Of course she cooked the muskrat, and eventually I would discover that the meat was absolutely delicious. The occasion of that culinary epiphany, along with Daddy’s red-eyed hissy over the thought of me eating “rat” [never mind that muskrats are vegetarians or that as a family we dined on “tree rats” (squirrels) with regularity] remains a treasured memory. This revelation came on a bitterly cold January day when deep snow led to school being closed. Never one to miss such God-given opportunities, I had been out rabbit hunting all day. On the way home I stopped by Aunt Mag’s, and as soon as I opened the door a wonderful smell greeted me. Inquiring as to what she had cooking, I received her standard enthusiastic response. “I’ve got me a big pot of stew going boy. Get you a bowl and have some.” I did just that and my, was it fine. With rich gravy, carrots, green peas, onions, and potatoes, along with tender chunks of meat of an unfamiliar color and texture, the savory dish was so scrumptious I had a second helping. Finally, as mystified by the contents as I was satisfied by the stew’s taste, I inquired: “What am I eating?” Aunt Mag had been waiting for that moment. Indeed, she had laid her trap with the same mental dexterity involved when she asked me about the comparative size of bream and butter beans. Had my dealings with furbearers shown half the canniness she displayed, I would have done far better in terms of trap line income. Cackling in sheer delight at my question while showing every one of her few remaining teeth, she replied: “Why boy, you be eating muskrat.” I should have known, but the occasion provided me a powerful personal lesson in the old-time way of utilizing what was available, whether it involved foodstuffs or something else, in the best way possible. The experience also offered me valuable insight about the inadvisability of turning one’s nose up at an untried sample of the good earth’s bounty. Aunt Mag died while I was off in college, her waning years of life slipping away just as the innocence of boyhood left me. Yet looking back the inescapable conclusion is that my friendship with this simple, impoverished black woman was one of the brightest facets of my boyhood. Interaction with her gave me first-hand exposure to the manner in which pride could triumph over poverty and a deep appreciation of the wonders associated with a staunch work ethic. I look back on the times spent with her with wistful longing, knowing full well she was one of the special characters who breathed life and joy into the youth of this son of the Smokies. She was as goodhearted a soul as ever graced the earth with her presence—poor but upstanding, never a stranger to hard work, and someone who, in an economic sense, struggled just to get from one week to the next. The advent of Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” lay almost a decade in the future during our time together, and “welfare” as mountain folks knew it involved nothing more than neighbors helping one another and those who were less fortunate. Aunt Mag gladly accepted gifts of food, worn-out clothing for making quilts, or things like the hand-me-down wood-burning stove my parents gave her. But she gave in her own right—selling free-range chickens to nearby neighbors at a bargain price, periodically bringing some fresh-cooked delicacy to our home, and graciously allowing me free rein when it came to snacking on whatever she might have cooked on a given day. She would take a hand up but not a handout. Somehow, while constantly dealing with the wolf of poverty howling at her door, Aunt Mag managed to get along just fine. She worked at simple tasks with a will, grew and dried or canned many of her basic food needs, feasted on eggs from free-range chickens, harvested various offerings of nature’s wild bounty, got help from neighbors from time to time, and, I strongly believe, lived a life stretching across almost a full century in which there was a great deal more gladness than sadness. My parents were among those neighbors who helped her, and in all likelihood they did so to a greater degree than anyone else. In addition to sharing surplus garden and orchard produce, they invariably remembered her at Christmas. Also, Daddy always saw to it that a couple of truck loads of wood scraps from Carolina Wood Turning Company were delivered to be used in the wood burning stove during the cold months. Both considered it a duty and an honor to help out whenever possible, and in terms of being part of a wonderful woman’s life, in enjoying the rewards of inner satisfaction, and through basking in some of the afterglow of brightness that encircled Aunt Mag’s existence like a halo, they were blessed in receiving far more than they gave. That was doubly true for me, and I’m still benefitting a half century plus after her death. Warm thoughts and longing looks backward attest to that. None of this should suggest that Mom and Dad were anything special when it came to philanthropy. They did what almost everyone on the small town and rural mountain scene did in the 1950s and 1960s—helped others when they could, knew the value of being good neighbors, and admired anyone who had a staunch work ethic. We weren’t well off by any stretch, although I’ll have to admit I didn’t really understand that until I went off to college and encountered folks who actually came from affluent backgrounds. We had enough to get along, and we shared when we could just as did almost everyone in the extended mountain community which was Swain County. In that regard today’s world is decidedly worse—there is far more crime, far less of a general work ethic, two and three generations of families who have basically lived at government expense, and a distinct decline in a sense of self worth. To me that is both tragic and sad, and I can just see Aunt Mag shaking her head, as she was wont to do when addressing something of which she disapproved, and saying, “That just ain’t right.” That’s enough of what Grandpa Joe would have termed moralizing and philosophizing though. My point is one which goes to the heart of traditional mountain lifestyles for proud folks no matter what their race. Aunt Mag was a sterling example of an admirable willingness to work, giving spirit, and deep-rooted integrity. Her life and lifestyle, while never ones of treasures and pearls, typified all that is good and gracious, enduring and endearing, in high country ways. Recipes I never think of Aunt Mag without associating her with food, for the example I offer of savoring her muskrat stew is but one of countless occasions when I stopped by for a bowl of whatever might be on offer. In wintertime I could count on some type of soup or stew, while in the warmer months the fare she offered might be a whopping slice of corn bread, corn dodgers, a biscuit adorned with home-made blackberry preserves, or maybe a whopping bowl of cobbler. You didn’t stop by Aunt Mag’s without being offered something to eat, and I for one seldom failed to take her up of the proffered vittles. Those are soothing thoughts to have in mind as I offer this month’s sampling of recipes. MUSKRAT WITH MUSHROOMS

1 muskrat cleaned (be sure to remove glands underneath legs) and cut

into serving pieces Combine the flour with salt and pepper. Dip the meat into the flour mixture. Heat the butter and two tablespoons of olive oil in a Dutch oven and brown the meat. Remove from the pan, add the remaining oil and sauté the onion and mushrooms until tender. Stir in the soup and mix well. Heat to a simmer. Return the meat to the pan, cover, and simmer until tender. OLD-TIME POKE SALAD

1 pound poke shoots Chop the poke shoots into one-inch pieces and combine in a large pot with one to two quarts of water. Boil for five minutes and then drain. Repeat twice more. Fry the bacon in a skillet until crisp. Crumble and add to the greens, along with salt. Add a little water and simmer until tender. Serve garnished with the chopped egg. BUTTERED SPRING GREENS

4 cups any type of wild spring greens (lamb’s quarters, creasy greens,

etc.) Sauté the greens in melted butter in a skillet until tender. Top with egg, bacon, green onions, and/or vinegar and serve immediately. WATERCESS SALAD WITH PARMESAN MUSTARD DRESSING

6 to 8 cups fresh watercress Wash the watercress and trim away largest stems. Whisk together the remaining ingredients in a small bowl. Toss the greens with the resulting dressing. HUSH PUPPIES Aunt Mag always had piping hot hushpuppies (and slaw) to go with fish. I have no idea how she made them, but they did contain corn and onion as is true of this recipe. She also often, though not always, included corn kernels in her cornbread. This was in the summertime when fresh corn on the cob was readily available.

1 ½ cups cornmeal mix Combine the cornmeal mix, flour and garlic salt in a bowl and mix well. Beat the onion, corn, egg, and milk in a separate bowl and add to the dry ingredients. Place the mixture in the freezer to cool while you heat cooking oil to 375 degrees in a deep fryer. Drop teaspoons of the batter, just a few hush puppies at a time, into the hot oil. Cook until golden brown, turning to cook evenly on all sides. Makes about 30 largish hush puppies (recipe can be doubled). Thank you for subscribing to the

Jim Casada Outdoors

newsletter. |

||||||

|

Send mail to

webmaster@jimcasadaoutdoors.com with

questions or comments about this Web site. |