SWEET SEPTEMBER

One of my favorite outdoor writers, Robert Ruark, makes a comment somewhere in his classic work, The Old Man and the Boy, to the effect that one of the appealing aspects of September was that once Labor Day had come and gone all the “willies off the pickle boat” went home. He offered that thought through the “Old Man,” but along with the departure of the hordes of summer visitors to the part of the world where I grew up, the Great Smokies, September offered something else truly special. It marked the opening of a new hunting season, the beginning of the end of heat and humidity, and a general uplifting in spirits. As Grandpa Joe used to suggest, “there’s something about a chill in the air of a morning and a hint of fall you can almost smell that puts pep in an old man’s step.” Now that I’m roughly of the vintage that Grandpa was when he offered that particular tidbit of wisdom, about all I can say is, that as usual, he was pretty much on the mark.

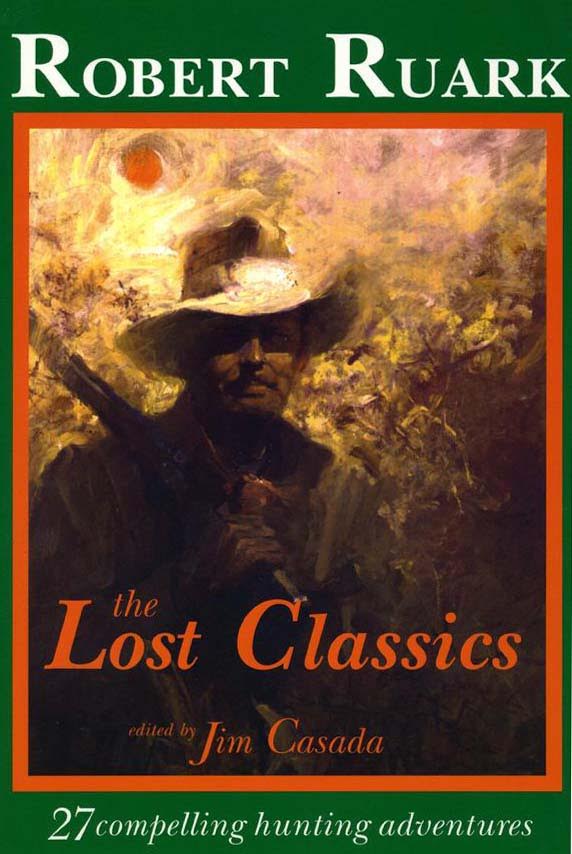

THIS MONTH’S BOOK SPECIALS

Mention of Ruark leads directly to this month’s special books offers. Several years ago I brought together 27 of Ruark’s timeless tales, including ten “Old Man and the Boy” stories, which had never previously appeared in a book. They had only been published in magazines many decades ago. The result was The Lost Classics of Robert Ruark, which, along with the 27 stories, includes my lengthy essay on the great writer, editorial commentary, a nice selection of original photographs, and a substantial bibliographical note. The book normally sells for $35 plus $5 shipping but I’m offering it for this month for $30 postage paid. Also, if you are a Ruark fan, be sure to browse my extensive list of books by and about him.

Also, since I apparently failed to get it listed anywhere on my website, let me once again mention a new reprint of Sam Hunnicutt’s enduring classic, Twenty Years Hunting and Fishing in the Great Smokies. I wrote a lengthy new Introduction for the book, which has until this reprint been almost impossible to access thanks to extreme rarity. Now you can get it (and I’ll gladly sign and inscribe the book if you wish) for $20 plus $5 shipping. Old Sam wasn’t ever going to be a candidate for a Nobel Prize in literature, and in fact this work represents about the closest thing imaginable to an English teacher’s nightmare. Yet it rings with authenticity and the author was without question a sportsman for the ages. To join him on one of his adventures in the expansive Deep Creek drainage is to find yourself in a world of wonder.

ADVENTURES IN AUTOBIOGRAPHY

My gardening is largely done for another year. I didn’t plant a fall garden. There are turnips aplenty for me, as well as the deer, in food plots on my hunting property. Since I’m now home alone it just didn’t seem worth the trouble to put in my usual autumn garden truck. Most of the neighbors with whom I share garden produce don’t care for the likes of broccoli, cabbage, chard, and cauliflower, and I’m tired of fighting deer, so I’ve packed it in until spring. I dug the last of the Kennebec potatoes this morning, and all that’s now left are some lingering tomatoes (I’ll have enough to last me until first frost) and okra.

Normally at this point I’d delve more deeply into my memories of September and what the month has meant to me over the course of my life, and certainly a small portion of that would include fall gardening as well as wild bounty from nature. I haven’t forgotten that aspect of things, and you’ll find the entire selection of recipes for this month devoted to that wonderful fruit that was such an integral part of my youth, the apple. Primarily though, this month and for some months to come I want to indulge what regular readers will realize is my unending penchant for meandering down side trails and checking out literary rabbit holes. Thus the heart of this month’s newsletter will be the first in a series of offerings which are autobiographical in nature.

Periodically someone asks me how I became a writer, and earlier today I exchanged e-mails with a fellow writer (Rob Simbeck, whose talents far transcend any ability I might have) about the whole nature of the beast. From time to time over the years I’ve touched on the subject of my slow emergence as a writer, mainly in this newsletter or in newspaper columns offering words of appreciation to folks who helped shape my career in one way or another. Indeed, as you’ll see from my “Doin’s,” in a few weeks I’ll be attending a special celebration for the man who was my mentor in undergraduate school. I can think of two occasions where I’ve been interviewed on the subject of becoming a writer. One appeared as an offering on the blog of my good friend, distant relative, and webmaster, Tipper Pressley. You can read her presentation by clicking here.

Similarly, an enterprising student at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, Alexander Teller, visited me several years ago for an interview. On October 30, 2013, he turned on a tape recorder and for 52 minutes I rambled, reminisced, and tried to give him an overview of my emergence as a writer. If you have been having trouble sleeping, want to verify the fact that never mind an ample quantity of education my hillbilly accent stuck with me like beggar lice, or simply have pretty much run out of anything to do, you can read an introduction to the material by Barbara Friedman and gain access to audio of the interview at this link.

What really brought me to this point, however, was a straightforward and insightful question from a newsletter reader, Gordon Bickers. He indicated that “when I read the stories about your family it makes me curious about the path you took that led you to writing and how you ended up where you are today.” His query got me to thinking about the entire matter and I realized that maybe a series of snippets about my emergence as a writer would be appropriate, particularly since I might in many ways seem a most unlikely candidate to have become a writer.

It will also give me a grand opportunity to thank a bunch of people who, consciously or otherwise, influenced me as mentors, guides, inspirations, or in some other fashion. Then too, I’ll add at the outset that I’ve been mighty lucky to have known a great many good folks, had some wonderful teachers, made a passel of friends in the world of communication, and actually lived a good bit of a life which was a boyhood dream. My fellow writers have uplifted me, at times filled me with envy, encouraged me, but most of all, helped me understand both the gladness and sadness integral to the writing life.

THE FORMATIVE YEARS—PART ONE

The fact that my earliest, most enduring childhood memories revolve around hunting, fishing, food folklore, gardening, closeness to nature, and mountain folkways suggests that in my case at least, the old adage about the “child being father of the man” certainly holds true. Many examples come to mind.

*The first fish I ever caught, a rather small bream which I insisted on keeping (clearly the concept of “release to grease” was a part of my perspective on fishing from day one). Momma, with the best of intentions, carried it a short way up the steep, rock-laden bank on Fontana Lake where we were fishing and for some reason put it under a rock no bigger than the bream. Predictably it flopped a bit and down the bank it came, all the way back to watery freedom. According to Daddy, who loved to relate the story, my howls of anguish would have awakened the dead.

*The first sizeable fish I ever caught. It was a catfish, again from Fontana Lake. Our family had joined another family for a camping trip on the reservoir’s shoreline. Daddy and I, along with the man in the other family, decided to do some night fishing for bream. The two men were in a boat a few feet from shore while I had a prime spot astride a lakeside stump. All of us were catching bream with some regularity, and I had gotten the knack of using the lengthy cane pole with which I was fishing to hoist them ashore. When I got another bite though, my “airmail delivery” to the bank didn’t work. Instead, the fish tugged so hard the tip of the cane went in the water, and I began to be worried about being dragged into the lake.

Daddy, no doubt laughing as he gave verbal instructions, told me to “hold on, keep fighting him,” and to be sure to stay seated with my legs locked around the stump. I followed his instructions and after a couple of minutes he got the boat to shore and came over, flashlight in hand, to offer assistance. Eventually I managed to manhandle (well, more accurately, boyhandle) a catfish that probably would have gone about 10 pounds, to shore. According in my father, and again the story was one he loved to relate, my assessment of the whole situation was: “Boy, catching a big one sure does make a fellow’s legs tremble.”

*I have particularly fond memories of my first trout on a fly. It came after what were no doubt trying times involving extraordinary patience on the part of my father, and honesty compels me, 66 years after the fact (I was nine when I caught the fish), to admit it was pretty much happenstance. I somehow managed to cast a fly to a likely spot and a rainbow of 7 or 8 inches hit it. Obviously it was a trout that needed to be removed from the gene pool, and that was precisely what happened. I proudly ate my first trout, duly dressed up in a cornmeal dinner jacket, that evening. If that offends readers who are of the catch-and-release persuasion, about all I can say is that trout were a regular part of family diet throughout my adolescent years. Incidentally, that moment, which took place near the Bryson Place on Deep Creek, deep in the heart of the Smokies, remains so bright that I feel confident I would still recognize the little pool.

*Fishing came first, simply because Daddy felt comfortable with giving me a hand-me-down South Bend Tonkin fly rod well before I was allowed to shoot a gun, but by the age of 12 I owned my first gun (a Stevens Model 220A 20 gauge choked tighter than Dick’s hat band). However, the first of many landmark moments in the field came a couple of years earlier. Today’s youngsters are, in my opinion, being done a disservice by starting out on deer or turkeys. I think small game in general and squirrel hunting in particular provide much finer apprenticeships, and that was the way I learned the hunting ropes.

*My first squirrel was taken with a borrowed .410 gauge hammer gun, and the hammer on it was so tight I needed both hands to pull it back. How I did that on a chilly October morning when a squirrel showed up at daybreak without scaring the bejeebers out of the bushytail I’ll never know, but somehow I managed it and made a telling shot at the quarry as it eased down the side of a hickory bedecked in all its golden-leafed glory. To this day I could walk to the ridge where I killed it. The tree is probably long gone but it’s still public land in the Nantahala National Forest and the setting is in my mind forever.

*It took a bit longer to get the first rabbit and the first quail thanks to overexcitement on my part and the unsuitable nature of the aforementioned 20 gauge. I’m sure Daddy bought the gun simply because he could get it at the right price, and I still own it, killed my first-ever turkey with it, and treasure the inexpensive little single shot in a manner monetary worth doesn’t measure. That being said, it was ill-suited for birds or rabbits because of the tight pattern it threw. Maybe that wasn’t all bad, because in time and after the misery of many misses I became deadly on running rabbits and at least decent on quail and the occasional grouse.

That’s enough “firsts” for this time around, and next month I’ll touch on some early educational experiences, the first money I earned, and random recollections of what it was like to be a boy growing up in Swain County, North Carolina, in the 1940s and 1950s.

**********************************************************************************

JIM’S DOIN’S

Recent weeks have been quiet on the home front. I enjoyed a couple of dove shoots—not a lot of birds but wonderful food and camaraderie—over the first week of the season. With a couple of buddies I’ve also checked deer stands on my property, cut shooting lanes, and have things in good order for opening day just a short way down the calendar road. I’ll also be doing a lot more traveling in the coming weeks (see schedule below).

On the work front, I’ve got a couple of pieces in the Summer issue of Carolina Mountain Life (my regular “Mountain Wisdom and Ways” column deals with “Traditional Stack Cakes” and includes a recipe which I share below, while a feature profiles “Cratis D. Williams: Mr. Appalachia”). Speaking of Williams, who is widely recognized as the father of Appalachian Studies, any reader interested in the mountain ways of speech and tales from yesteryear should make a visit to http://artsandsciences.sc.edu/appalachianenglishtranscripts.html. There you will find 10 hours worth of transcripts and the original recording of folks from my highland homeland in the Great Smokies who were recorded by linguist Joe Hall in the late 1930s and early 1940s. You can read transcripts or listen to tales told by legendary hunter and fisherman Mark Cathey, a distant relative of mine; the noted Tennessee character, Wiley Oakley; and accounts from lots of ordinary folks from the hills. Horace Kephart may have dismissed these “branch-water people” and demeaned them with the worst sort of stereotyping in Our Southern Highlanders. I think a session at this website will readily convince you that these were a distinctive, interesting, and delightful people from a region to be cherished rather than sensationalized.

My feature, “Wielding the Magic Wand,” appears in the Sept./Oct. issue of South Carolina Wildlife and offers, as the title suggests, a ruminative and hopefully literate look at fly fishing. My series of profiles of mountain characters continues in Smoky Mountain Living magazine, with the most recent being a profile of Olive Tilford Dargan, a fairly prominent writer whose best-known book is From My Highest Hill, set squarely in Swain County, the place of my birth. The next issue of the magazine will carry my piece on Sam Hunnicutt, an incredibly hardy son of the Smokies whose book, Twenty Years Hunting and Fishing in the Great Smokies was recently reprinted with a lengthy new Introduction I wrote. As I have already noted above, copies are available for $20 plus $5 shipping. I’ll be speaking on Hunnicutt about the time this newsletter reaches you in a presentation at Western Carolina University (see schedule below). I’ll have an essay on “Yankees Come A-Calling” in the next issue of the Charleston Mercury magazine as well as coverage of the culinary joys of persimmons along with a feature on mountain balds in the fall issue of Carolina Mountain Life. Finally, yesterday’s e-mail brought the welcome and uplifting news that I was among the winners in this year’s excellence in craft competition of the Southeastern Outdoor Press Association. I won’t get any details until the awards banquet at the organization’s annual meeting in October, but it’s always exceptionally gratifying when I win anything in this keenly contested annual competition.

MY SCHEDULE

September 28—I’ll be at Western Carolina University speaking to that institution’s Friends of the Library group in the first of what is a planned annual event. It will celebrate the reprinting of Sam Hunnicutt’s rare book, Twenty Years Hunting and Fishing in the Great Smoky Mountains, for which I wrote a lengthy new Introduction (as covered in the June newsletter). I still have copies of the book available for $25 postage paid. It is my understanding this event is open to the public.

September 29-30, October 1—Attending the annual meeting of the South Carolina Outdoor Press Association in Florence, SC. This gathering enables me to see a lot of longtime friends, enjoy some grand company, and get my batteries recharged a bit through interaction with my peers. Private event.

October 1—Quail hunt at Moree’s Sportsman’s Preserve in Society Hill, SC (www.moreesreserve.com). This is a top-notch operation I included in an article for Quail Forever magazine which covered my choice of 10 of the top shooting preserves in the Southeast. Any time such as this when I can watch staunch bird dogs at work and be a part of activity which calls back joyous days of yesteryear brings me delight (and rest assured I’ll carry a gun afield which is infinitely more functional for quail than the 20 gauge mentioned above which was my first gun).

October 15-16—In Bristol, TN to present a guest lecture to a group at King University, my undergraduate alma mater, and to attend an event honoring Dr. Bill Wade, my college mentor and a man who was special in the formative stages of my life. Private events.

October 18-22—Attending the annual meeting of the Southeastern Outdoor Press Association (SEOPA) in Kentucky. I’ve been a member of this organization for well over three decades and twice have served as its president. Some of my best friends in the world, and a number of professionals to whom I look for advice and inspiration, are fellow members. In a jam-packed period of seminars, testing new products, interacting with editors, and having some wholesome fun (there’s always pickin’ and grinnin’ for an evening or two, and while my musical talents are non-existent I’m a world-class grinner), I’ll be uplifted and invigorated in a way that doesn’t happen any other time of the year. SEOPA is my organizational home and the fact that I’ve never missed a meeting since joining tells you something about how much I value my membership. Private event.

Nov. 11-12—I’ll be in Middleburgh, Virginia to give a talk in connection with a special hunt/fundraiser being sponsored by the National Sporting Library and Museum and hosted by some of the organization’s board members. As some of you may recall, I had a research fellowship at the NSLM a few years back and was so impressed that I’ve remained closely involved with them in a variety of ways. They are doing a splendid job in preserving essential aspects of our nation’s grand hunting heritage. Private event.

********************************************************************************

RECIPES AND REMEMBRANCES: THE COOKING CORNER

APPLE TIME

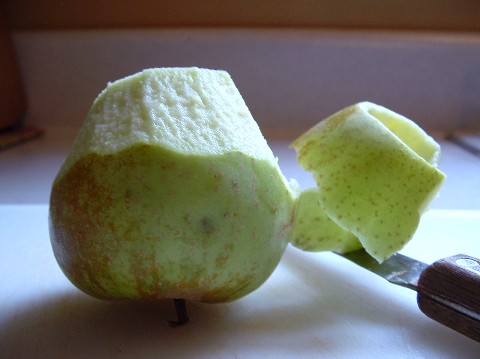

When I was a boy we had a small apple orchard. It only amounted to a half acre or perhaps a bit more but the trees (Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, Stayman, and one volunteer which had no name but produced fine cooking apples that kept well) were highly productive. That was thanks in large measure to Dad’s meticulous care of them—judicious annual pruning, multiple sprayings, and attention to every detail at picking time. Of course he was meticulous about most everything, a characteristic of his I wish I had emulated in greater detail.

At any rate, year after year, with rare exceptions when a late frost killed the blooms (the trees weren’t ideally situated at all, being on a south facing slope, but somehow they survived frost virtually every year), we had an abundance of apples. How I loved, at this time of year, to pick one still wet with dew as I headed off to school. I’d pluck another one in the afternoon when I got home, and of course apples figured prominently indeed in our family diet. During my teenage years Momma had a stated goal of canning 100 quarts of apples each autumn. We would eat them almost daily through the late fall and winter, sometimes hot with a pat of butter added but most often as a cold fruit dish. Some would be dried as well while others were carefully stored in an earth-floored basement that was, for the most part, dug out by Daddy with some help from me. Along with baskets, there were a couple of big home-made bins where he stored apples. One of my chores was to go through them once a week or so to remove any that showed signs of going bad. Most years we would still have fresh apples, although long since mellowed to the point where the chin-drenching juice each bite provided in September was no more, well into January.

Getting apples ready for canning was an “all hands on deck” chore, often performed on the porch of an evening if it wasn’t too cool. If memory serves my sister didn’t care for the peeling, quartering, cutting out the core, and putting the pieces in a big dishpan full of slightly salty water to keep them from turning brown until they were canned. She had a pronounced tendency towards temporary deafness at such times. On the other hand, it was a chore I enjoyed. After all, I’ve always found it comforting to be putting food by for times to come, and in this instance whenever you peeled a particularly promising Red Delicious you could eat a quarter and put the other three pieces in the dish pan.

Momma usually dried a bushel or two for use in fried pies, but my Grandma Minnie, perhaps harkening back to pre-canning days, dried far more. Grandpa Joe also had apple trees, so like our immediate family they had the joy of “apple time” come September. Grandma was always a great one for making stack cake (see recipe below) and that delicacy, along with fried pies (all see below), claimed the bulk of the apples she dried each fall. These delights form some of my fondest memories of her culinary wizardry, and rest assured her cooking skills were at the wizard level.

I still love apples and will regularly buy some when I’m in my native North Carolina mountains. One place in Haywood County, Barber Orchard, has a stand where along with a wide variety of apples they sell all kinds of baked goods utilizing them. A stop there this time of year is mandatory (it is just off Highway 19/74, the Smoky Mountain Expressway, as you head up the mountain towards Balsam southwest of Waynesville).

In praise of the noble apple, the fruit which without question loomed largest in dietary matters during my boyhood, all of this month’s recipes are devoted to apple dishes. Here they are.

SMOKY MOUNTAIN STACK CAKE

In mountain communities stack cakes were commonly associated with weddings or birthdays, but in my case I’ll always think of the delicacy in terms of homecoming—my coming home. Even after I was grown, gone away (you don’t normally say gone from home, because mountains remain the home of the heart), and married, anytime Grandma Minnie got word I was coming for a visit she would make a stack cake—seven layers high, with applesauce from apples she had dried slathered between each layer. The thin layers readily soaked up the moisture from the applesauce, and she made a point of letting the cake sit for three days before presenting it to me. Over those 72 hours there was a wonderful mixing, mingling, and marrying of flavors with the end result being toothsome fare that words can’t describe and no hoity-toity restaurant can match.

THE SAUCE

Rehydrate four or five packed cups of dried apples. You can do this by placing them in a pan of water overnight to soak, pouring off any excess water the next morning, or by cooking them in a saucepan. For the latter, bring enough water to cover the apples to a rolling boil and then reduce the heat to a low, slow simmer. Stir frequently and if the sauce becomes to dry, add a bit of water. You want the apples to be quite thick, about the consistency of apple butter. While they are simmering, add brown sugar to taste to sweeten (this will vary appreciably depending on the sweetness of the dried apples being used, but a cup should be about right) and cinnamon. Grandma always used the tiny little red cinnamon candies you could once find in any store, but I don’t remember seeing them in years, but if you use the powdered variety a teaspoon will be what you want. A generous pinch (if you have to have measurements, I reckon a hefty pinch is about a half teaspoon) of ginger and nutmeg can be added if you wish. If the sauce remains too chunky when it is ready, mash it up thoroughly.

THE CAKE

One key to a top-notch stack cake is very thin layers of cake that are nice and level and can be stacked atop one another (hence the name). Grandma always had seven layers, maybe because the number is considered a lucky one or perhaps simply because that was the way she did it. She didn’t measure much of anything, unless you can bring precision to a dash, dibble, pinch, or similar words, but she sure know how to get things right. I’ll try to simplify matters a bit and use specific measurements. Incidentally, she always baked eight layers, two at a time. That gave her an extra if one cracked or something went wrong, but that seldom happened. What did happen is that someone, often in my younger years it was me, had a thin, delicious layer of cake to drizzle with a bit of honey or top with berry preserves and enjoy with milk.

- 5 cups all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1 cup of granulated sugar

- 2/3 cup vegetable shortening or lard (I’m sure Grandma used lard but today vegetable shortening is much more readily available)

- 1 cup molasses (you can substitute a cup of brown sugar but molasses gives the cake a “tang” (for want of a better word) you won’t get from brown sugar

- 2 lightly beaten eggs

- 1 cup of buttermilk (make sure it is shaken well)

Preheat your oven to 350 degrees and grease then flour nine-inch cake pans. Depending on the size of your oven and how many pans you have you’ll likely need to bake in shifts of two or four layers.

For the batter, thoroughly blend (with a whisk) the flour, baking powder, baking soda, and salt in a large bowl. In a second sizeable bowl, beat the shortening, sugar, and molasses with an electric mixer set to medium speed until the mixture is smooth and thoroughly creamed. Of course our forebears didn’t enjoy the luxury of blenders, but plenty of gumption and elbow grease did the job quite nicely. Next, add the eggs, one at a time, beating well as you add them. Then add the flour mixture to the moist ingredients by thirds, alternating as you go with gradual addition of the buttermilk. Once everything is well mixed, the consistency of the batter should be comparable to that of cookie dough. If it is a bit too thin, add a little more flour.

The batter will be too thick to pour into the baking pans. Instead, put it on a cutting board or other floured surface (Grandma always used waxed paper) and divide it into seven or eight equal-sized sections. Then, with your hands floured, spread and pat the dough into the cake pans. It will be quite thin, perhaps a half inch or so. Before putting it in the oven, use a fork to prick the dough some. Grandma used to indulge in some fancy di-does of fork work with the top layer for decoration. Bake until golden brown and firm (probably 15 minutes but watch closely). The cake layers will not rise much if at all.

The penultimate (that’s one of what a high school English teacher of mine called a $10 word—it means next to the last) step is making the stack. You do that by slathering a thin layer of sauce atop each cake layer as it comes from the oven. You’ll need to exercise some care to keep everything nice and level as the stack grows. The final step involves nothing but sheer patience. As I’ve already indicated, a proper stack cake needs to cure. That means letting it sit for a couple of days while the layers soak up the sauce and the whole melds into a soft, moist thing of wonder. Grandma always made extra sauce, and if you were so inclined (and I was) you could spoon some additional sauce atop your generous slice of stack cake. It takes quite a bit of preparation, but a stack cake is food for the gods.

FRIED APPLE PIES

See instructions above for the sauce for stack cake. The same sauce can be used to make fried pies or, alternatively, cook fresh apples to make sauce. If you take the latter approach just make sure the sauce is extra thick.

Prepare pastry your favorite way or, if in a hurry, take the lazy route and use prepared pie pastry from the store. Either way, you need a round section of pastry lightly dusted with flour on the bottom. Cover one half of the pastry round with apple sauce and then fold the other half over. Carefully crimp the edges with a fork and then fry on a non-stick skillet, in a cast-iron pan, or on a pancake griddle, turning once and browning both sides. Add a pat of butter to each fried pie as it comes from the pan.

In the kind of company I keep they’ll be eaten as fast as you can make them.

APPLE COBBLER

This simple apple cobbler recipe takes only a few minutes of prep time. The end result, topped with cream, milk, or vanilla ice cream, is a delight beyond compare.

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- 1 cup sugar

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1 cup milk

- ¼ cup butter, melted

- 3-4 cups apples, quartered, cored, and chopped or sliced into small pieces (leave the skin on). Fuji or Golden Delicious are personal favorites, but if you like a bit of tartness, try Granny Smiths or Jonathans.

Combine flour, sugar, baking powder and milk; stir with a wire whisk until smooth. Add melted butter and blend with the whisk. Pour batter into a 9 x 13-inch baking dish and pour apples evenly over the batter (do not stir). Bake at 350 degrees for 30 to 40 minutes or until golden brown.

APPLE QUAIL

As I note in my schedule, I’ll be enjoying an outing at Moree’s Sporting Preserve as a special way to welcome in what is probably my favorite month, October. Hopefully one result of that time afield will be some quail for the table. If so, here’s one of my favorite ways to enjoy this epicurean delight.

- ¼ cup flour

- ½ teaspoon salt, or to taste

- 1/8 teaspoon paprika

- 6 quail—breasts and legs

- 2 tablespoons butter (use the real McCoy)

- 1 cup chopped sweet onion

- 1 teaspoon chopped fresh parsley

- ¼ teaspoon dried thyme

- 1 cup apple juice

Mix flour, salt, and paprika and lightly flour quail pieces. Melt butter in a heavy frying pan and brown quail. Push quail to one side of the pan. Add onion and sauté until tender (add another tablespoon of butter if needed). Add parsley, thyme and apple juice. Stir to mix well and spoon juice over quail while bringing all to a boil. Reduce heat, cover and simmer until quail are tender (about an hour). Serve quail on a bed of rice with sautéed or candied apples on the side.

APPLE VENISON CROCKPOT ROAST

- 3 to 4 pound venison roast

- Salt and black pepper to taste

- 1 (10 ½ ounce) can double strength beef broth

- ½ can water

- ¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon

- 3 teaspoons cream-style horseradish

- 4 apples, sliced, cored, and quartered (Fuji and Gala are good varieties for this dish)

Combine the broth, water, cinnamon, horseradish and apples in a sauce pan and bring to a boil while stirring. Place venison roast in crockpot. Pour heated sauce over the roast and cook on low 6 to 8 hours or until roast is tender. Use juice from the sauce in crockpot to pour over slices of the roast.