AUGUST—DOG DAYS, DUST DEVILS, AND MAGICAL MEMORIES

If I suggested something to the effect that August ranks among my favorite months, I’d be going well beyond the bounds of literary license into the realms of downright lies. In fact, second only to February, the month is my least favorite. It’s hot and humid, still evokes distant memories of the dread associated with resumption of school, most of the time trout won’t hit worth a lick, the best of the year’s gardening has come and gone, and meaningful hints of autumn still seem a distant dream.

Yet even in the worst of times on the yearly calendar there are random recollections of the best of times—the sight and sound of a dead ripe watermelon splitting wide open at the first insertion of a home-made butcher knife; munching on sweet-tart ground cherries; skinny dipping in the cold, clear waters of Deep Creek; the bittersweet end of summer romances as visiting girls who spent vacations in the high country return to wherever they came from soon to become distant and vague memories; or catching catfish in the Tuckaseigee River while using worms dug in Aunt Mag’s chicken lot.

That final memory opens a door to a warm flood of special days and special ways. Aunt Mag, an ancient black woman who had been born in the midst of the War of Northern Aggression, was a wonderful friend who could cook like nobody’s business and with whom I had an ongoing arrangement connected with being allowed to dig worms in her chicken lot in return for an occasional mess of fish. She was loving, poor as Job’s turkey, hard-working, proud, and endowed with a subtle sense of humor. A good example is connected with our worms-for-fish arrangement.

At one point in our relationship (I was probably 11 or 12 years old) I dug worms and went fishing for several days in a row without delivering her anything for the frying pan. After a few days she asked me: “Boy (she always called me boy), ain’t you been catching anything?” I told her that while I had been catching some panfish all of them had been quite small and accordingly had been released.

Her response was: “Were they bigger than a butterbean?” I readily allowed that while small, they were appreciably larger than that. “Well boy,” she said, “I’ll eat a butterbean.” I got the rapier-sharp dig underlying message in loud, clear fashion. Henceforth bluegills and knottyheads, no matter how small, went on the stringer. Her philosophy was “if they are big enough to bite they are big enough to eat.”

Thoughts of my interaction with Aunt Mag often revolve around chickens. Her yard birds, which was what she and most everyone else called them, were an important part of daily life for her and her widowed niece, Elma. They ate the eggs daily and occasionally feasted on the meat. The chickens, in addition to providing food, kept their yard and garden free of insects, served as a sort of living alarm system when anyone approached, and furnished rich fertilizer which grew wonderful vegetables. They also flocked to me any time I showed up, because my activities in digging worms unearthed all kinds of goodies for their diet.

YARDBIRDS IN MY YESTERYEARS

Musing on such matters leads to the general subject of yard birds, and that is the focus of this month’s essay. It’s a trip down a long, winding road into the mountain past, and what I wouldn’t give for a batch of eggs from free-range chickens or a hen, baked to a golden turn, where I could dig into the carcass and feast on the eggs in the making lining the body cavity. For now though, fond recollections of boyhood experiences with yard birds and their place in Smokies’ life will have to suffice.

Anna Lou Moore, toddler feeding chickens

Three generations or more ago chickens were, for all practical purposes, as much a part of the normal mountain homestead as bedsteads or corn cribs. Look at vintage black-and-white photos of home places and it is surprising how often the image will show free-range chickens scratching in the yard. Chickens had a myriad of virtues. They were to a remarkable degree self-sufficient—capable of getting a goodly portion of their living on their own in the form of insects, worms, seeds, and in season, garden vegetables. As long as they were free range, and most were, their menu was wonderfully varied and grit for gizzards to do their grinding took nothing but pecking. Moreover, one of their favorite foods was “scratch feed,” which in yesteryear essentially translated to various versions of corn—leavings from winnowing or sifting, leftover cornbread, grains rubbed from cobs, and the like. Provide supplementary food as needed, make sure that water was available, and chickens pretty well looked after themselves.

Along with some supplements to chickens’ diet during the period between the first killing frost and spring’s greening-up time with its abundance of tender shoots and sprouts upon which to feed, the biggest needs of a flock in terms of human support focused on three things. Chickens sometimes needed protection from a host of potential enemies; their domiciles required occasional cleaning; and they had to have human assistance with housing basics connected to cover, roosting areas, and nesting places. In the latter case though, I remember many of Grandpa’s flock roosting in trees, and particularly during spring nesting season there was always an obstreperous old hen or two who wanted to wander off and lay her eggs in some hidden spot on the ground as opposed to one the perfectly good boxes provided in the hen house.

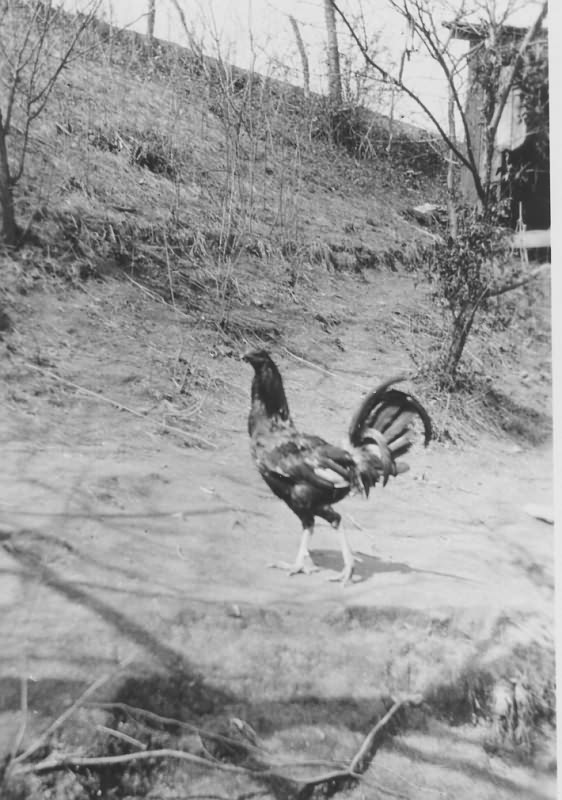

Game cock

Vigilance on the part of the farm family took care of enemies. Never mind that raptors are federally protected in today’s world, there was a time when every hawk was a “chicken hawk.” Grandpa Joe would have had my hide if a hawk showed up and, if I happened to be armed, I hadn’t taken a shot at it. In truth though, I don’t remember any problems in that regard. I strongly suspect that the little bolt-action .22 rimfire he own took care of avian predators in short order.

Mammalian predators were a bigger, more frequent threat. Rats, weasels, ‘coons, skunks, foxes, and ‘possums could go after both chickens and eggs. Egg-sucking dogs and egg-eating snakes could likewise wreak havoc. For every adversary though, there was an answer. It only took one moment of interaction with an egg which had been “blown” (had its contents removed without breaking the shell) and filled with hot pepper sauce to cure dogs and snakes of any future interest whatsoever in eggs. Traps or, more commonly, the family shotgun, dealt with other attacks on chickens. Since they raised an unholy ruckus anytime a predator showed up, the flock in effect a built-in alarm system to provide intruder alerts.

Along with Grandpa Joe, I had first-hand dealings with a variety of predators threatening his flock of chickens, but my favorite recollection connected to the general subject of raids on chickens came through one of his endless store of tales. Cougars (mountain folks almost always called them “painters”) were long gone from the Smokies by my boyhood, but Grandpa had a memorable experience with one when he was a young man. The big cat had made nocturnal raids on his chickens on multiple occasions and with devastating results. Determined to deal with the situation, Grandpa began keeping a shotgun loaded with buckshot by the bed.

Only a few nights later he was awakened by a ruckus in the chicken lot. He grabbed the gun and headed in that direction with only the moon and stars to guide his footsteps. As he reached the chicken house either a slight noise or a sixth sense alerted him and he looked toward the top of the rough shed where the chickens stayed at night just as the panther sprang at him. He literally “wingshot” the massive feline in mid-air and it died in a buckshot-riddled heap at his feet. Grandpa loved to tell that tale, and he punctuated it with descriptions of what a panther’s scream sounded like (“a dying woman”) and details suggesting he never came closer to death. Needless to say his starry-eyed understudy was an eager audience of one every time talk turned to “painters.”

It may well have been guineas which alerted Grandpa to the cougar’s presence, because nothing can quite match them when it comes to a farm alarm system. A flock of guineas makes a finer guard dog, at least in terms of alerting the household to visitors (welcome or otherwise), than the most vocal fice or mountain cur ever known to man. They create an unholy ruckus and don’t seem to know the word “Stop.” Many mountain households raised guineas with that aspect of their behavior in mind. They in no way match chicken when it comes to table fare, and their eggs are inferior as well. However, if you wanted a hard-shelled egg for use in “egg fights” at Easter time (a contest where the pointed ends of two boiled eggs were knocked against one another, with the winner getting to keep the broken egg of the loser), a guinea egg was a sure winner.

Like chickens, guineas ranged free for the most part, and both could make a fine living, at least in the warmer months of the year, simply by roaming about a mountain home place. Still, you had to keep an eye on them, and daily gathering of eggs was a part of this ongoing human vigilance. For example, chickens absolutely love tomatoes, and I fondly recall Grandpa Joe allowing them unimpeded passage in his mixed patch of varieties such as Brandywines, Rutgers, and Marglobes along with both the prolific red tommytoes and the little pear-shaped yellow ones he grew. That didn’t happen until Grandma Minnie had canned and made all the soup mix she needed, but by late August that would have been accomplished and tomatoes would be in gradual decline. Grandpa would have quit tying them to stakes or else the plants would have grown out the top of their supports. It was time to give the yard birds their turn, and there would still be enough tomatoes high on the stalk to meet slicing needs for dinner and supper.

Cock with a dictator strut

More than once I heard Grandpa say: “You’ve got to pay close attention to yard birds when they get on maters. They’ll eat ‘em to the point of half starving to death while doing so (there isn’t a great deal of protein or food value in tomatoes). They’ll also go off their egg-laying duties.” Of course, no matter what the diet, laying activity dropped dramatically during the Dog Days of late August and early September. Where a few months earlier the chicken lot would have sounded like a cackling Tower of Babel, now there might be no more than four or five hens out of the entire flock of perhaps three dozen proclaiming to the world how proud they were of having laid an egg.

As long as access to tomatoes was reasonably controlled and they weren’t damaging other garden truck, chickens were allowed to roam pretty much where they wished. Their menu was wonderfully varied, and like Grandpa I enjoyed watching them going about their daily business. At times the chickens could be flat-out comical. Such was especially the case when Grandpa and I enjoyed one of our grand summertime pleasures—getting down to business on a watermelon in mid-afternoon after an arduous session of work. We would devour the brilliant red, juicy goodness and compete to determine who was the most accurate or had the greatest range in seed-spitting contests. Watching the chickens scramble out for each shiny black tidbit at such times would often find both of us laughing uproariously.

Eating the seeds was nothing more than a clean-up operation, but other dining preferences of free-ranging yard birds had significant benefits. They kept unwelcome insects such as potato beetles, grasshoppers, bean beetles, crickets, and packsaddles under control without any need to resort to spray, dust, or other chemical agents of control. Grit to digest such comestibles was there for the pecking, and I know of nowhere in the mountain soil where grit of a suitable size, whether it is rocks or sand, isn’t immediately available.

Most mountain yards in distant yesteryear were completely bare, and there were reasons for this. It kept ticks, fleas, chiggers, and other unwelcome insects at bay, and frequently there would be a grove of black walnut trees growing around a homestead to help in that regard. The roots of walnuts are a bit toxic, and as a result most plants don’t grow particularly well under them. Add a busy housewife wielding a broom from time to time and the passage of a regiment of chickens marching through on a regular basis, and the time and effort of mowing simply didn’t come into play. That was important, because grass-mowing efforts would have been completely wasted in terms of food productivity or contributions to survival.

Along with literally being capable of scratching out a goodly portion of their living, chickens were multi-purpose recycling machines. Along with serving as a sort of permanently-on-call Orkin man, another ancillary benefit they provided came in the form of manure. You had to be careful with chicken droppings—they are so high in nitrogen overly generous applications will burn a plant up—but properly used they made wonderfully effective fertilizer. I hated that aspect of dealing with yard birds, because shoveling up the manure in roost areas and around coops was smelly, nasty business. Still, it had to be done and somehow it seemed I was the worker of choice whenever it was time to clean out the chicken lot.

Chicken on the table was an important part of Smokies life, but that was normally a luxury reserved for holidays, guests, church suppers, and Sunday dinner. No dinner on the grounds or meal associated with a revival or other special religious event would have been complete without chicken aplenty, and I love Rick McDaniel’s description, in An Irresistible History of Southern Food, in which he describes barnyard fowls as “The Gospel Bird.”

The preliminaries to episodes of kitchen legerdemain such as those Momma performed on a weekly basis didn’t involve going to the meat market and selecting your bird. Instead, the chicken was already on the property awaiting the not-so-tender attention of those residing on the farm. Typically, procuring a bird for the table involved one of two approaches, although, as we will see below, Grandpa Joe had an alternative approach. Either you waited until after fly-up time and lifted a bird from the roost or else a bunch of chickens would be cornered against a fence and one of them seized. In both cases, in the immediate aftermath of apprehension came execution. That was accomplished by wringing the bird’s neck (the way Grandpa killed them) or by a swift stroke of an axe or hatched while the bird’s neck lay on the chopping block where kindling was split.

About as mad as I ever saw Daddy was an occasion when I somehow talked Momma into letting me do the chopping. She held the intended victim by the legs, with its neck across the section of log we usually used to split kindling, and I attempted to whack its neck with a hatchet which had been a Christmas gift a few weeks earlier. I don’t know whether Momma turned the chicken loose too soon or I hit a mislick (each of us accused the other when explaining the scenario to Daddy). You frequently hear the phrase “running around like a chicken with its head cut off” used to describe weird or untoward behavior, but in this instance the situation involved a hen running around with its head only partially cut off. Daddy expended a great deal of energy in apprehending the maimed hen, and that ended my chicken-killing career for several years.

Although it took the better part of a half day, from the failed execution until Daddy came home from work and captured the chicken, in the end its fate was like that of every other yard bird destined for the family table. Whatever the means of the bird’s demise, once it had stopped flopping it was time to prepare the carcass for cooking. The bird would be immersed in a bucket of scalding hot water, plucked and gutted, and readied for the kitchen. If it was a pullet or frying size chicken this would mean the additional step of cutting it up into legs, thighs, wings, breast (in halves) and back. Baking hens, of course, remained whole.

The daily routines and behavioral patterns of yard birds fascinated me as a kid. At times their singular lack of intelligence astounded me, although old chestnuts about being so lacking in brainpower that they will drown looking up at a heavy rain are just that—old chestnuts, and rotten ones at that. But I was captivated by the way some slight change in their humdrum routine could result in a tremendous racket, the manner in which a hen would defend her chicks with astounding aggressiveness, and a seemingly complete inability to recognize certain types of danger while going bonkers when faced with other threats.

The finest example of their frequent obliviousness to peril revolved around the manner in which Grandpa Joe caught chickens for table use. His method always garnered my rapt attention, and whenever possible I liked to accompany him “to get a chicken.” He wanted no part of lifting them from the roost or chasing them down. “That’ll put ‘em off their egg laying duties,” he’d say, “and you know we can’t have that.” Instead, he had worked out a method of capturing chickens which was ingenious in its simplicity and almost unbelievable inasmuch as yard birds never learned of the imminent jeopardy connected to an old man carrying a lengthy cane pole.

Grandpa observed his chickens, which might range in number from three dozen to 50 during the spring growing season when peeps were making the transition to adulthood, with astuteness. Cockerels would, once they reached full growth, immediately become candidates for the family table. Pullets, on the other hand, were left unmolested in order to move into their predestined duties as egg producers. This gave them a stay of execution, but once the time of year rolled around for baked chicken (Thanksgiving and Christmas) their gender and activities as laying hens no longer offered guaranteed security. Thanks to daily observation, Grandpa knew exactly which hens had been lethargic layers. They would be the object of his interest when it came time to bring Grandma Minnie a hen (maybe two or three if a big family gathering was in the works).

Carrying a handful of scratch feed along with his “chicken fishing pole,” as he styled it, he would scatter the feed on the ground, step back, and carefully observe the resultant scramble to peck up every bit of grain. He had his pole at the ready when the right moment arrived. Other than being longer, it was a cane pole of precisely the same sort he used to fish in the Tuckaseigee River which ran by the house, chicken lot, and hog pen. Maybe 15 to 18 feet, it was equipped quite simply with two or three feet of the black nylon line used on casting outfits of the day tied to the pole’s tip. The other end of the line had a small fish hook (size 10 or 12) affixed to it.

Grandpa would “bait” the hook by pinching a small piece of bread onto it. He then held the pole aloft at a 45-degree angle, well above the hens, and waited until his target was off by alone, far enough away from the other hens to make sure she would be the only one able to grab his “bait.” He then adroitly dropped the baited hook on the ground right in front of the intended victim. Invariably there would be a quick peck of the sort which gave rise to the phrase “like a chicken on a June bug,” and the hen would be hooked. Grandpa then began pulling her toward him with a hand-over-hand motion as he moved down the cane pole from its base to the end holding the chicken. Once the hen was within reach he grabbed her neck, gave in a quick twist, and that was it. He would remove the hook after the flopping was over.

The amazing thing about this rather gruesome but eminently practical scenario is that the other hens never learned. If he needed two hens for the kitchen Grandpa could repeat the performance without so much as a sign of angst from the feathered congregation brought together by his dispensation of scratch feed. It probably says something about my psyche and certainly does nothing to endear me for organizations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, but I thoroughly enjoyed the entire process. I might also note that it was high effective, and Grandpa’s chickens lived far better lives than those eaten by anyone who purchases their meat at grocery stores or dines on fare from places such as Kentucky Fried Chicken or Bojangles. If you eat chicken and are somehow dismayed by the way it got from the coop to the family table in days gone by, you really are at a rather distant remove from understanding the cycle of life.

For all that they brought dining delight when served on mountain tables, in the grander scheme of overall dietary practices, it wasn’t really chickens that took primacy of place. It was the eggs they produced. Eggs were a key component of diet, standard fare at breakfast, vital for all sorts of baking, useful for a boiled egg snack, available for pickling in times of real surplus, and regularly utilized for deviled

Lyrics from the old Bobby Bare country classic, “Chicken every Sunday, Lord, chicken every Sunday,” held true for many a mountain family. Certainly it was the case throughout my boyhood and beyond, and mere thoughts of Momma’s fried chicken awaiting our return home after church services can set my salivary glands into involuntary overdrive to this day. That’s a fitting thought on which to close, and below are a number of chicken recipes dating back to my Smokies’ boyhood.

MOMMA’S FRIED CHICKEN

I’ll acknowledge at the outset that try as I might I’ve never quite been able to match Momma’s fried chicken, and I don’t think anyone else has either. Grandma Minnie was a wizard in the kitchen, but when it came to frying chicken Mom had her beat. My brother Don fries first-rate chicken as well, but somehow it’s never quite as succulent or melt-in-your-mouth tender as Momma’s was.

1 or 2 whole chickens, cut into pieces (legs, thighs, wings, and breasts) with skin left intact

1 or 2 eggs beaten

Salt and pepper to taste

Flour

Cooking oil

Drench each piece in the egg wash and then coat thoroughly with flour (mix your salt and pepper in with the flour) before placing in piping hot oil in a cast iron spider (I think cooking in cast iron makes a difference, but don’t ask me to prove it). Cook slowly until thoroughly brown.

All of this seems normal enough, but it is Mom’s final step that made all the difference. Once she had all the chicken fried and placed atop paper towels to drain a bit, she would clean the cast iron skillet and put the fried chicken back in it. She would then turn the oven on at low heat (200 degrees or maybe a bit less) and put the skillet in the oven. She normally did this just before heading off to church on Sunday. After church she would pop the skillet out of the oven once she had readied the rest of the meal. I don’t recommend leaving it for a couple of hours the way she did, or at least not until you figure out the right timing and temperature of the oven. Being in the oven seemed to do two things—cook away some of the surplus grease and make the chicken so tender it almost fell from the bones and melted in your mouth. Mercy was it fine!

AFTER THE FEAST SOUP

1 baked hen carcass with some saved chicken scraps

1 large onion, peeled and quartered

4 ribs celery with leaves, chopped

1 large carrot, scrubbed and cut into chunks

2 whole cloves garlic

1 bay leaf

Water to cover

Remove skin from the carcass. Place in a stock pot and surround with onion, celery, carrot, garlic and bay leaf. Cover with water and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer, covered, for two hours. Refrigerate stock and remove fat which accumulates on the top. Remove all meat from bones and save.

8 cups stock (add canned chicken broth if needed)

2 cups milk

4 medium potatoes, peeled and diced

3 carrots, peeled and diced

3 ribs celery, diced

1 cup frozen or canned lima beans

2 ounces small shell pasta

2 cups fresh, chopped spinach

1 cup frozen green peas

Meat from carcass

¼ cup fresh parsley

½ teaspoon dried basil

1 teaspoon fresh black pepper

Salt to taste

1 cup evaporated milk

2 tablespoons flour mixed with 4 tablespoons water (optional)

Cook stock, milk, potatoes, carrots and celery for a half hour. Add lima beans, pasta, spinach, peas, turkey, parsley, basil and pepper to the soup and cook an additional 20 minutes. Remove from heat, season with salt if necessary, and stir in evaporated milk. Return to low heat, stirring often. Do not let soup boil. Thicken with flour/water paste if desired.

12 hearty servings

CHICKEN PIE

6 tablespoons butter

6 tablespoons all-purpose flour

¼-1/2 teaspoon black pepper

2 cups homemade chicken broth (make your own stock, save broth from stewing a chicken, or you can use store-bought chicken broth)

2/3 cup half-and-half or cream

2 cups cooked chicken

Prepared pastry for two-crust pie (or, preferably, make your own)

Melt butter; add flour and seasonings. Cook about a minute stirring constantly. Add broth and half-and-half and cook slowly until thickened. Add chicken and pour into pastry-lined pan. Top with rest of pastry and pinch edges together. Bake at 400 degrees for 30-45 minutes or until pastry is browned. An alternative is to add cooked vegetables, such as corn, green peas, and carrots, to the cooked chicken and make a pot pie.

CHICKEN PATE

More often than not, giblets from the hens we ate went into gravy, but occasionally the organ meats would be set aside and saved for use on their own. I loved the rich taste of the giblets and here is a simple way of enjoying them as an appetizer, snack, or even sandwich spread. I personally prefer it to liver mush from pork (and that’s a treat I thoroughly enjoy).

Giblets (heart, liver, gizzard) from several chickens

Two boiled eggs

1 sweet onion

3-4 cloves garlic

Butter or olive oil

Salt and pepper to taste

Clean and chop the giblets into small pieces and sauté in a large frying pan with the chopped onion and garlic using butter (my preference) or olive oil. Then mince thoroughly in a food processor and allow to cool. Boil two eggs then peel and chop them finely. Add salt and black pepper to taste (I like lots of black pepper). Mix minced giblets and eggs thoroughly and press into a bowl or mold and chill until solid. Serve with toast wedges, crackers, or as a sandwich spread.

CHICKEN AND DUMPLINGS

1 large (mature hen or rooster) chicken cut into pieces (legs, thighs, wings, halved breast, neck, back)

1 large sweet onion

4-5 large carrots scraped and cut into two-inch sections

4 stalks celery cut into sections

8 cups chicken broth, equivalent amount made using chicken base, or the equivalent from chicken stock you have made

Salt and black pepper to taste

Green peas or spinach

Cook the chicken pieces, carrots, onion, celery and seasoning in a large stew pot for an hour. At the end of the hour add ¾ cup of green peas or a double handful of washed spinach and cook for an additional 15 minutes. At the end of the cooking process you can thicken the chicken and broth, if desired, with a bit of cornstarch. I personally like the broth somewhat “runny” because it seems to mix best with the dumplings. Add cooked dumplings to the chicken-vegetables-broth and serve piping hot.

DUMPLINGS

½ cup milk

1 cup flour

2 teaspoons baking powder

½ teaspoon salt

Slowly add milk to dry ingredients. Drop by teaspoons into boiling liquid. Cook for 15-20 minutes or until dumplings are done in the center.

GARDEN OMELET

I somehow associate springtime with eggs, although properly fed and cared for hens will lay reasonably well throughout the year. Beyond greening-up time being when some ancient switch of procreation is triggered not only in chickens but most birds, part of my line of thinking unquestionably goes back to boyhood days of gathering them with Grandpa Joe. The hens always laid well at this season, although Grandpa had to stay alert to keep up with wayward hens bent on raising a brood their way. That meant two or three headstrong hens which eschewed the convenient nests he provided in the chicken house for hidden places elsewhere. I loved to accompany him on his daily mission to gather eggs, and when a search for outlier nests was included in the mix, it almost became a scavenger hunt.

There were always eggs aplenty in springtime, and the extras came in handy in a variety of ways. Some of the hens would be allowed to continue their setting to hatch and raise a brood, but mostly we just gathered the eggs. Some were given to family members, some were sold (by Grandma, an arrangement I never quite figured out since Grandpa did all the work but she kept the income as her own private stash), and that period of the year saw a bounty of cake baking thanks to the plentiful supply of eggs. There was also the extra demands posed by children (like yours truly) wanting a bunch of Easter eggs for their baskets.

In short, a super-abundance of eggs didn’t pose any problems. Eggs are sometimes described as the perfect food, and Grandma Minnie certainly knew how to put them to might tasty use in a wide variety of ways. However, I don’t recall either Grandma or Momma ever making omelets.

For my part, I love them, and a favorite supper of mine is a two- or three-egg omelet incorporating whatever is available in the way of vegetables from my garden or that of nature. Choices might involve asparagus, spring onions, ramps, spinach, Swiss chard, morel mushrooms, water cress, or other items. Add salt and pepper to taste, some sharp cheese, a bit of butter, or maybe crumble in a couple of slices of bacon fried to a crisp, cook the omelet so the outside edges show a hint of brown, and you have some mighty fine eating. I have an omelet pan, but you can make an omelet in a large frying pan. Just empty the beaten eggs and other ingredients into a large, well-greased skillet, and once the bottom is firmly cooked, flip half over to make a half-moon shape and complete cooking. HINT: Adding a tablespoon or so of water to the mix when you beat the eggs up produces a fluffier end product.

CHICKEN AND EGG SALAD

This is a fine way to utilize left-over stewed or bake chicken and/or a surplus of eggs. It’s good whether eaten atop a lettuce base, with soda crackers, or in a sandwich.

2 cups chopped chicken (or use blender to pulse it to a coarse but not overly minced state)

4 large eggs, boiled, peeled, and coarsely chopped

¼ cup chopped sweet pickles

Salt and black pepper to taste

2-3 tablespoons of mayonnaise (more if needed for right consistency)

1-2 tablespoons of prepared mustard (amount will depend on how much you like the tang of mustard)

Generous sprinkling of paprika (optional)

Prepare the chicken, eggs, and pickles then place together in a large mixing bowl. Add the mayonnaise, mustard, salt, and pepper. Stir thoroughly with a large wooden spoon. Refrigerate until ready to eat.

HINT: One of my favorite kitchen tools, and it’s one I must admit I’ve never seen in a Smokies kitchen, is the Inuit knife known as an ulu. Its handle and rounded blade make it faster, safer, and more functional than any butcher knife.

*********************************************************************************

JIM’S DOIN’S

I don’t have a great deal going on this month but that will change, in what for me is dramatic fashion, come September. Meanwhile I’ll be providing a regular column for a new publication, Bryson City Magazine, which will launch this fall; I’m privileged to have been asked by my dear friend, Rob Simbeck, to write a foreword for a book which will bring together a collection of his tight, bright columns on creatures great and small which have appeared in the pages of South Carolina Wildlife for many years; and I’ll have a piece in that lovely magazine’s Christmas issue on decorations from nature. I just sent off a profile of the above-mentioned Aunt Mag to Smoky Mountain Living and I have other magazine pieces in the works.

Once September arrives I’ll launch a spate of travel which is quite at variance with my pattern in recent years. Conversations with a couple of medical people, prompting from my daughter, and input from friends have pretty well convinced me that it’s good for my state of mind to get away from the daily stress connected with my wife’s dementia. Accordingly, I’ll be giving the keynote address to the annual meeting of the Great Smoky Mountains Association in Gatlinburg, speaking on four skilled photographers—Jim Thompson, Dutch Roth, George Masa, and Kelly Bennett—who captured the loveliness of the Park before it was actually created. I also plan to attend a conference I haven’t missed in three plus decades, the annual gathering of members of the Southeastern Outdoor Press Association as well as being present for the conference of our little state group, the South Carolina Outdoor Press Association. Throw in a high school class reunion and that translates to more travel in two months than I’ve done in two years.

THIS MONTH’S SPECIAL

Recently a loyal reader, avid turkey hunter, and longtime customer sent me an e-mail introducing a fellow turkey hunter to whom he had recommended some of my writing. In that e-mail he most graciously commented that my book, Remembering the Greats: Profiles of Turkey Hunting’s Old Masters, was in his opinion one of the five finest books ever written on the sport. He likely is far wide of the mark, but I’m proud of the book and was certainly flattered by the comment. That work is this month’s special offer, at $27.50 postpaid. At that cost I can’t take PayPal orders (too much of a bite out of my fiscal hide) so they should be by mail with payment by check. South Carolina customers will need to include state tax at 7% ($1.93).